Following back-to-back victories against Lazio and Chievo Verona, Udinese stand on the brink of achieving the improbable dream of qualifying for the Champions League for only the second time in their history. They only need one more point to guarantee their entrance through the “gates of paradise”, as Europe’s flagship competition was described by their down-to-earth coach Francesco Guidolin, but the last game of the season is against this year’s champions Milan, so this objective is still far from a fait accompli.

For a self-professed small club from the provinces, this would be a notable feat, especially as they only finished in 15th place last season and started this year’s campaign with four consecutive defeats, languishing in last place after six games. Before the season kicked-off, most pundits had predicted mid-table as the height of their aspirations, but Udinese’s free-flowing brand of attacking football (only Inter have scored more goals so far this season) has brought them many new admirers, as well as the record number of points in Serie A for Le Zebrette (little zebras).

Indeed, the venerated owner Giampaolo Pozzo proudly stated, “We play the best football in Italy”, a claim that was difficult to argue with after a series of scintillating performances, including an astonishing 7-0 win against Palermo (in Sicily), a thrilling 4-4 away draw against Milan and a richly deserved 3-1 victory against Inter. This is all the more impressive as Udinese are a young team of many nationalities with players emanating from all over the globe.

"Cristian Zapata - Colombia's finest"

Thus, the team that overcame Chievo featured four South Americans, most obviously the brilliant Chilean Alexis Sánchez, but also the pacy wing-backs, Mauricio Isla (also from Chile) and the Colombian Pablo Armero, plus the formidable centre-half Cristián Zapata (also from Colombia).

It also included two players from the African continent: midfielder Kwadwo Asamoah, who played every match for Ghana in the 2010 World Cup, and the Moroccan international Mehdi Benatia. Finally, the team contained three Europeans from smaller nations: the new Swiss captain, hard-working midfielder, Gökhan Inler, and his compatriot Almen Abdi, plus the coveted Slovenian goalkeeper, Samir Handanovič, who recently tied the league record of saving six penalties during the course of one season.

However, the bandiera of the team is the captain Antonio “Totò” Di Natale, who has been at the club since 2004, resisting all overtures to move away, including an offer last summer from Juventus. He was the top scorer in Serie A last season with an incredible 29 goals, an exploit that he is almost certain to repeat this season, as he is currently leading the capocannoniere charts with 28 goals.

"Toto Di Natale - not just for Christmas"

However, Pozzo has also paid tribute to the efforts of Guidolin, “Praise should be divided between him and the team. If you don’t have a great coach, nothing will be achieved.” After working minor miracles last year when he guided Parma to an unexpected 8th place in their first season back in the top flight, Guidolin somewhat surprisingly returned to Udinese for his second spell after a brief period in charge in 1998/99. As befitting the Friuli area, which is famous for its hard-working ethic (as epitomised by Fabio Capello), Guidolin’s motto for the team has been “humble but ambitious.” Nevertheless, after a distinctly unpromising start, Guidolin proved himself capable of making big decisions, when he “took a gamble” by moving the mercurial Sánchez from the wing to the middle, playing just behind Di Natale, which has turned out to be a masterstroke.

Despite being one of the oldest football clubs in Italy Udinese have never really won anything of note, though they do seem to have firmly established themselves in the top tier, having competed in Serie A for sixteen consecutive seasons, a record only matched by Milan, Inter, Lazio and Roma.

Furthermore, they have qualified for Europe eight times in the last 15 years, the highlight being when Luciano Spalletti’s team, built around the goals of Vincenzo Iaquinta and that man Di Natale, reached the Champions League in 2005, when they were eliminated at the group stages by a late goal from Barcelona. They also had a good run in the late 90s, when they qualified for the UEFA Cup four years in a row, initially under Alberto Zaccheroni, whose team was inspired by the prolific German striker Oliver Bierhoff. Most recently, Udinese got as far as the UEFA Cup quarter-finals in 2008/09 before being knocked-out by Werder Bremen.

"Giampaolo Pozzo - 25 years and counting"

The main man behind Udinese’s rise during this period has been the owner, Giampaolo Pozzo, an Italian businessman who bought the club at a difficult moment in 1986, when it was embroiled in a betting scandal, resulting in a nine-point penalty that meant relegation to Serie B.

History repeated itself in 1990, when the authorities imposed a four-point penalty after they deemed a phone call to Pozzo’s counterpart at Lazio on the eve of an important match as evidence of untoward activities. Since that time, Pozzo has relinquished his role as club president, leaving the day-to-day running to Franco Soldati and his son Gino, who has proved a veritable figlio d’arte (as the Italians say), following in his father’s footsteps to perfection. However, Giampaolo still very much remains the power behind the throne.

In the 90s Pozzo implemented a strategy that has become the envy of other clubs. Udinese have become famous for their skilled operations in the transfer market, especially their ability to find hidden talents all over the world, which they develop and later sell for large gains. The reputable Italian financial newspaper Il Sole 24 Ore approvingly described this business model as running “like a Swiss watch.”

In reality, Udinese have been forced to be innovative, as their budget is much lower than the leading Italian clubs. It is fair to say that Serie A is not easy for provincial clubs, as the likes of Milan, Inter, Juventus and Roma have traditionally benefited from substantial financing by industrialist owners and superior television and commercial deals. It is also difficult for the smaller clubs to attract Italian talent into their primavera, hence Udinese’s decision to cast their net further afield.

"Samir Handanovic - loves a penalty save"

The club set up a global scouting network of around 50 observers with hundreds more local contacts in order to identify the most promising young players before they had become fully established and attracted the attention of the larger clubs. Furthermore, they have focused on “alternative” markets in Africa and South America that are relatively unexploited in order to purchase youngsters at a reasonable price. They usually buy from second tier countries, examples being Chile and Colombia in South America (as opposed to Brazil and Argentina) and Switzerland and Slovenia in Europe.

This arrangement also works well for the players, who accept low salaries in return for further development, experience in one of Europe’s best leagues and the opportunity to put themselves in the shop window. Although Udinese’s policy of acting as a stepping stone for their best players may not make their fans happy, there’s no doubt that the profits from the regular sales makes a huge contribution to the club’s financial self-sufficiency.

The sensational Alexis Sánchez is a great example of how carefully Udinese nurture their talent. Although the club bought him as a precocious 16-year old talent in 2006, he did not arrive at Udinese until the summer of 2008, having been loaned out twice as part of the development process: initially to the Chilean club Colo Colo, then to River Plate in Argentina to give him experience abroad, but not too far from home.

"Guidolin - where did it all go right?"

Udinese have bolstered their strategy by forming a partnership with Granada, a club playing in the Spanish second division, where they loan youngsters that need playing time, such as the Ghanaian Jonathan Mensah. Given the Friuli club’s connections with the South American market, it is no coincidence that they opted for a club in a Spanish speaking country to park their players. In total, Granada currently have an amazing 14 players on loan from Udinese.

In fact, one of the logical results of Udinese’s approach is that they end up having an extremely large squad, so they absolutely need to loan out a vast number of players every season (earning them €3.6 million in 2010). Including the players at Granada, I make the current total 63, though I may well have lost count. This is the sort of “wheeler dealing” that makes Harry Redknapp look like a rank amateur.

The problem with all these ins and outs is that it makes it difficult for Udinese to progress to the next level, but their consistent presence in Serie A’s top ten over the years is ample proof of their ability to remain competitive despite the constant departures. It is strange to say, but they have effectively sold their way to the top without weakening their squad, as seen by this small club providing no fewer than eight players at last year’s World Cup: Di Natale, Sánchez, Isla, Asamoah, Inler, Handanovič, the Italian Simone Pepe (since loaned to Juventus) and the Serb Aleksandar Luković (since sold to Zenit St. Petersburg).

Of course, like every other club, Udinese’s record in the transfer market is not perfect and they have bought their fair share of duds (also suffering from a fake passport scandal in 2000), but overall their policy has been a solid money-maker. The scouting network reportedly costs €4 million a year, but this investment has produced some staggering financial results.

In the last decade, Udinese have received over €206 million from sales in the transfer market. Deducting purchases of €94 million during the same period gives net proceeds of an astonishing €112 million. In most years since 2005, there have been at least a couple of big money sales, including the likes of David Pizzarro (Inter), Marek Jankulovski (Milan), Per Krøldrup (Everton), Vincenzo Iaquinta (Juventus), Sulley Muntari (Portsmouth), Andrea Dossena (Liverpool), Asamoah Gyan (Rennes), Fabio Quagliarella (Napoli), and last summer, Gaetano D’Agostino and Felipe (both to Fiorentina). It’s a seemingly endless production line of players who were bought cheaply, but sold on for large sums.

Even as the transfer market stagnates elsewhere, Udinese have somehow managed to keep ahead of the others. Last year, their net sales were higher than any other club in Serie A, while the previous season they were only surpassed by Milan, thanks to the truly exceptional sale of Kaká to Real Madrid.

Over the last four years, their net proceeds of almost €60 million have been far ahead of other Italian clubs. In fact, only five other clubs had a net surplus in that period. To place Udinese’s performance into context, their net gains are higher than those other five clubs put together – that’s extraordinary.

And it’s not just the players who appreciate Udinese’s ability to develop individuals. Friuli has also proved to be an ideal environment for ambitious coaches with the two most eminent graduates in recent times being Luciano Spalletti, who has gone on to win the Russian League with Zenit St. Petersburg and the Coppa Italia with Roma, and Alberto Zaccheroni, who instantly delivered a scudetto to Milan.

The reason why Udinese are so concentrated on making money from player sales is immediately apparent when you look at how small their revenue is. Although it is the tenth highest in Italy at €41 million, leaving them in mid-table respectability (or mediocrity, depending which way you look at it) in the Serie A money league, it is streets behind the leading clubs. Last season, three clubs earned more than five times as much revenue: Inter €225 million, Milan €208 million and Juventus €205 million. Roma generate three times as much revenue at €123 million, while Fiorentina, Napoli and Lazio all have turnovers more than double that of Udinese.

This really puts Udinese’s performance this season into perspective, especially when you consider that a club with the same revenue, Sampdoria, has just been relegated. If they do manage to get into the Champions League, the gap to the leading European clubs becomes more like an abyss with clubs like Real Madrid and Barcelona earning ten times as much income.

This highlights the challenge that would face Udinese in Europe. As an example, when Sampdoria crashed out to Werder Bremen in the final qualifying round for the group stages, they were facing a team whose annual budget is two and a half times as high as their own. Another interesting comparative is that Udinese’s 2009/10 revenue was lower than every single club in the Premier League, so less than the likes of Burnley, Hull City and Portsmouth, who were all relegated to England’s second tier.

Other points stand out from the analysis of the revenue mix. Udinese get a very small proportion (9%) of their revenue from gate receipts with only two clubs having a lower percentage (Siena and Juventus). On the other hand, Udinese’s reliance on TV income is very high at 64%, even without European revenue.

The importance of player trading to Udinese’s business can be seen very well in the above graph. If profit on player sales is considered as “revenue”, its contribution has been notable in the past few years, averaging 35-40% of normal turnover since 2008. Put another way, the club makes six times as much from the transfer market as gate receipts. In fact, it makes almost twice as much from player sales as gate receipts and commercial income combined. This would be very worrying if Udinese had not shown that they are more than capable of maintaining this “revenue stream” year after year.

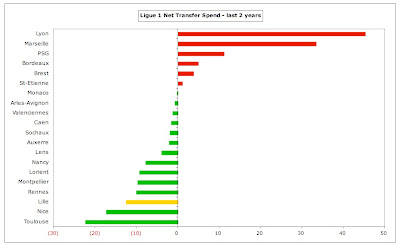

Of course, Udinese are not unique in their ability to generate profits on player sales, but they compare favourably to other clubs who are equally renowned in this area. For example, in the last three years Udinese made €78 million, which may be less than the €91 million earned by Lyon and €111 million earned by Porto in the same period, but in fairness those clubs do have a far higher spending capacity.

In spite of their low turnover, Udinese have managed to operate a sustainable model with cumulative net profits of €3 million over the last six years. After two years of solid profits in 2008 (€7.9 million) and 2009 (€6.9 million), the club did report a small loss of €6.9 million last year. There were a number of reasons for this decline: lower gate receipts, as there was no European competition in 2009/10, €1.5 million; increase in staff costs to strengthen the squad and a payment following the departure of former coach, Pasquale Marino, €4 million; lower profit from player sales, €7 million; and a €4 million tax payment on prior years’ profits.

Essentially, the profit and loss account reiterates the importance of profit on player sales, which is used to more or less balance the books. Obviously, whether this is sufficient depends on how much money is made from player trading. Last year, profit from player sales of €23.6 million was not enough to offset the €26.1 million operating loss, but in 2009 the higher profits on player sales of €30.9 more than compensated for the operating loss of €17.4 million.

Eagle-eyed financial observers may have noticed that the revenue figures used in my money League are lower than those used in the club’s own books. The reason for the difference is that Italian accounts report gross revenue, while I have shown net income, as this is consistent with the approach used in other countries. Therefore, I have excluded the following: (a) gate receipts given to visiting clubs €0.6 million; (b) TV income given to visiting clubs €4.3 million; (c) revenue from player loans €3.6 million. Adding the €8.5 million adjustments to the €40.8 million in my analysis gives the €49.3 million reported in Italy.

If we look at how Udinese compare to other clubs in terms of profit, a few points emerge. First, they are indeed one of the more profitable clubs with only five ahead of them over the last two years – when their result was a perfect example of how to break-even with an aggregate profit of exactly zero. Second, the significance of profit on player sales is yet again emphasised with only two clubs recording higher profit on player sales as a percentage of turnover (Parma and Genoa). Third, just look at the size of the losses made in then last two years by Inter €223 million and Milan €77 million.

Note that the profit on player sales used by La Gazzetta dello Sport are higher than mine, as they have only shown plusvalenze, leaving minusvalenze in costs. Very technical, but rest assured that the source data is identical.

By now, it should be abundantly clear to everyone that Udinese’s business model is hugely reliant on profit made by selling players, but, whisper it quietly, the winds of change may just be blowing at Udinese. Last week, Giampaolo Pozzo spoke of three factors that might grow the club’s resources outside its traditional prowess in the transfer market, namely the Champions League, television money and a renovated stadium. If these plans come to fruition, Udinese may be able to modify its celebrated strategy and hang on to its stars.

"Mauricio Isla - Udinese's other Chilean"

Along with his son Gino, he understands that for Udinese to grow, the club’s approach needs to be fine-tuned with more emphasis on other revenue streams. That does not mean that Udinese will totally jettison their “buy low, sell high” strategy, not least because they’re so damn good at it, but it does suggest that they realise that they need to do more financially to advance to the next level. As the owner put it, “We are fighting with the dagger between our teeth for the last slice of the TV money. Then, there’s the plan to improve the stadium. And Europe brings higher earnings.” Obviously, this will not be easy, but let’s look at each of these potential growth areas in turn.

Reaching the Champions League would be the biggest game changer. Last time Udinese qualified in 2005/06, they received around €12 million revenue: €9 million from UEFA’s central distribution (participation fees, prize money and TV income) and €3 million additional gate receipts. However, the sums available these days are considerably higher with the four Italian qualifiers last season earning an average of €29 million (Inter €49 million, Milan €24 million, Fiorentina €22 million and Juventus €21 million).

It’s also worth noting that while the Europa League would help boost funds, it is nowhere near as rewarding as the Champions League with last season’s three Italian representatives (Roma, Lazio and Genoa) only earning around €2 million each. Indeed, the team that actually wins the Europa League, having played countless matches, only receives €6.4 million. Udinese are well aware of this fact, having earned just €1.2 million from their UEFA Cup adventure in 2008/09, and Pozzo has spoken of the “big difference” between the two competitions, so it is very worthwhile securing that fourth place.

"Celebrate the good times"

The importance of qualification to Udinese’s plans has been underlined by the owner’s recent announcements. First, he said, “With the Champions, I would like to keep Sánchez and the other family jewels” and then went a stage further, “If we get into the Champions, then I will buy.”

Of course, they’re not there yet and have two more hurdles to clear. First, they have to cement their position in Serie A, taking at least a point from Milan, but this would only qualify them for the Champions League play-off round and they could face a very tricky tie to reach the lucrative group stage. Just look how close Spurs came to disaster in their match against the Swiss minnows, Young Boys Bern, before finally squeaking through.

The other obvious point is that it will be really hard for Udinese to qualify for the Champions League on a regular basis, especially as Italy will lose one of their four places from 2011/12, now the Bundesliga has overtaken Serie A in UEFA’s table of coefficients. In such an eventuality, Udinese would have to cope with a dramatic reduction in funds, as happened to them in 2007, when their revenue fell by more than a third from €44 million to €28 million, turning a €6.5 million profit into a €6.3 million loss.

Udinese’s domestic TV deal was worth around €26 million last season, having risen in 2008 when the new contract was introduced, but this pales into insignificance compared to the €90-100 million that Juventus, Milan and Inter have been earning from their individual deals. These vast differences have meant that the playing field in Italy has been anything but level, but years of protest finally led to a new collective agreement being implemented at the beginning of this season. We know that the total money guaranteed by exclusive media rights partner Infront Sports will be approximately 20% higher than before at over €1 billion a year, but it is still unclear what the impact will be on each club’s revenue.

There is a complicated distribution formula, which will still favour the bigger clubs, though there is likely to be a reduction at the top end. Under the new regulations, 40% will be divided equally among the 20 Serie A clubs; 30% is based on past results (5% last season, 15% last 5 years, 10% from 1946 to the sixth season before last); and 30% is based on the population of the club’s city (5%) and the number of fans (25%).

The larger clubs will lose out from the new arrangement, but the mid-tier clubs like Udinese will benefit. There is still a question over how the number of fans (worth 25% of the deal) will be calculated, leading to a major dispute between the larger clubs (represented by Milan, Inter, Juventus, Roma and Napoli) and the smaller clubs (represented by Udinese, Parma, Sampdoria, Palermo and Catania), even over which market research companies to use. Pozzo is at the forefront of this battle, as he understands the importance of the decision to the revenue of clubs like his. Whatever the final ruling, it seems reasonably certain that Udinese’s TV revenue will grow – the only question is by how much.

However, Udinese’s real Achilles heel, like so many Italian clubs, is their paltry match day income. Last season’s gate receipts of €3.6 million were exactly the same as the amount Manchester United generate in a single match at Old Trafford. In fact, the so-called theatre of dreams took in €122 million of match day income last season, which is an incredible 34 times as much as Udinese.

That is partly explained by Udinese’s ongoing struggle to attract spectators. In fact, last season’s average attendance of 17,356 was only the 13th highest in Serie A. Given the relatively small size of Udine (population 175,000), that’s perhaps not overly surprising, but it’s hardly conducive to financial stability at a football club. This also underlines the club’s need to work the transfer market, as the profit from one good player sale (€8 million) is the equivalent of Udinese tripling their gate receipts.

Nevertheless, the club has announced plans to renovate the Stadio Friuli, though interestingly the work will actually reduce the stadium’s capacity from the current (restricted) 30,667 to a more realistic 22,000. Although one objective is to increase revenue, the underlying objective is to make the stadium a “theatre of football”, which will be more attractive to local fans and tempt the crowds back. Pozzo explained, “We don’t want a cathedral in the desert.”

"Design for life"

The initial plans were for a multi-purpose development, including restaurants, hotels, gyms and a commercial area, but this met with opposition from existing concerns. Instead, the local council has in principle approved a modern, two tier stadium with all seats fully covered and the athletics track eliminated, bringing the spectators closer to the pitch, the inspirations being the Stadio Luigi Ferraris in Genoa and the Stadio Dino Manuzzi in Cesena.

There will be more hospitality areas and the club will be allowed to stage a number of events, such as music concerts and rugby matches, which will generate additional revenue, but this is not likely to be significant in my opinion. There has been no mention to date of any naming rights.

Unlike Juventus, the “new” stadium will not belong to the club, but continue to be owned by the council. In return for Udinese paying all the construction costs, which are estimated to be around €25 million, the council will give the club a 65-year lease and reduce the annual rent, which is currently €200,000 a year. The other condition that Pozzo has imposed is that the building work must commence this summer, so that the new stadium is ready in time for the start of the 2013/14 season.

It had been hoped that the new stadium would be used for Euro 2016, but that tournament has now been awarded to France. UEFA’s minimum capacity for hosting such international events is 34,000, but the plans allow for the Stadio Friuli’s capacity to be increased at a later date by adding a third tier if necessary.

There is also room for growth in the club’s commercial revenue, which actually slightly decreased in 2010 to €11.1 million, one of the lowest in Serie A. The shirt sponsorship deal with Rumanian car manufacturer Dacia (owned by Renault) was extended two years in July 2009, but is only worth €1 million a season, a lot less than other Italian clubs: Milan – Emirates €12 million, Inter – Pirelli €9 million, Juventus – BetClic €8 million, Roma – Wind €7 million, Napoli – Acqua Lete €5.5 million and Fiorentina – Mazda €4 million.

Those clubs also receive higher sums from their kit suppliers than the €1.1 million Udinese get from Lotto Sports (Inter – Nike €18 million, Milan – Adidas €13 million, Juventus – Nike €12 million, Roma – Kappa €5 million and Napoli – Macron €4.7 million). However, one of the indirect benefits of qualifying for the Champions League is higher commercial income, as sponsors see greater exposure.

Given the low revenue, the club has admitted that it is under “continual pressure to contain costs”, which effectively means the wage bill. Udinese have done a reasonable job here with wages rising in line with revenue since 2005, both with growth around 55%. The problem is that as the turnover is so small, even a minor increase in the wages has an inordinate impact on the important wages to turnover ratio, e.g. a €4 million rise in 2010 caused this ratio to worsen from 58% to 71%.

Nevertheless, Udinese’s wage bill of €31 million is still one of the smallest in Serie A and looks utterly insignificant compared to those of the “big four”, who appear to be playing in a different league altogether: Inter €234 million, Milan €172 million, Juventus €138 million and Roma €101 million. This is a double-edged sword for the club: on the one hand, it’s financially prudent, but on the other hand it makes it difficult to hold on to players. Then again, given Udinese’s high reliance on profits from player sales, maybe this is not an issue.

Only one player at Udinese, Di Natale, receives more than €1 million annual salary with the next highest paid being Sánchez €0.7 million and Zapata €0.65 million. Totó’s value looks even better, if you consider that he has scored exactly twice as many goals this season as Zlatan Ibrahimović, who is on €9 million a year.

Bonus payments can also have an impact on successful clubs, but Udinese’s players have apparently only been promised €3 million in total if they remain in the top four, described as a “cherry on the cake.”

Player amortisation, the cost of writing down transfer fees over the length of a player’s contract, is not that high at €14 million, but this is material when your turnover is only €44 million. Indeed, the increase in 2007 was noted in the accounts as one of the reasons for that year’s loss.

Udinese’s net debt has been steadily increasing in the last four years and now stands at €36 million after deducting €1 million cash. This includes €13 million bank loans and €24 million from a factoring arrangement with Unicredit. Although the bank loans are clearly not excessive, it is worth noting that only three Italian clubs have higher balances: Milan €164 million, Inter €71 million and Juventus €33 million.

This is nothing to really worry about, especially as Udinese have net balances owed to them on transfer fees of €24 million, made up of €28 million owed to other clubs and a hefty €52 million owed by other clubs. Given the way that Italian clubs do business with many stage payments, this is by no means unusual, but the fact that the balances are so high is a direct result of Udinese’s buying and selling strategy. There shouldn’t be any major issues here, though the exception that proves the rule was the dispute with Portsmouth over money owed for Muntari.

In fact, Udinese has one of the strongest balance sheets in Serie A with net assets of €38 million, only behind Fiorentina and Juventus. This fine achievement is actually under-stated, as the players are only valued at €48 million in the accounts, while the respected Transfermarkt website has estimated that a more realistic market value would be in the order of €111 million. No wonder Pozzo allowed himself to proclaim, “Fortunately the club is in the best of (financial) health.”

So what of the future?

In the accounts, the club confidently expects a “positive result” for 2010/11, based on the new collective TV rights deal and (stop me if you’ve heard this one before) “notable” profits on player sales in the 2010 summer window – already higher than the total achieved in the whole of 2009/10.

"Gokhan Inler - Swiss efficiency"

Nevertheless, other clubs will inevitably still apply pressure on Udinese to sell their talented players this summer. There would be no shortage of suitors for Sánchez, including Barcelona and Manchester United, though Manchester City are understood to be in pole position with a reported bid of €35-40 million. In some ways, although no club would want to lose a player of his calibre, this would be the ultimate vindication of the Udinese strategy, as they only paid €3 million for the little maestro. Even Guidolin admitted, “He is destined to join a top club, considering the quality he has shown for some time.”

At least a deal of this magnitude would mean that Udinese would have no need to sell any of the other players, though Asamoah, Inler and Zapata are all in demand. For the moment, Pozzo is holding firm, “Our wish is to strengthen the squad, but it’s up to the players. However, this time nobody wants to leave.” Furthermore, the players’ values should go up if they perform well in the Champions league.

Those may be the words of an astute salesman, but, as we have seen, Udinese should soon have more money from other sources. Pozzo again: “I know we are regarded as a selling club, but now things have changed, as the money in Italy will no longer just go into the pockets of the usual 4-5 big clubs.”

"Happy days for Asamoah"

Longer-term the advent of UEFA’s Financial Fair Play Rules should theoretically benefit well-run clubs like Udinese, but paradoxically it also poses two threats to their strategy. First, it could reduce the value of transfer fees, as clubs do not want to carry high amortisation costs – indeed, transfer spending was down almost 30% in Europe’s major leagues in 2010. Second, more clubs will try to emulate Udinese’s success at developing youth players, so the competition will become even more intense. This is why Udinese have started to invest in facilities to house teenagers, as they search for even younger players.

The chances are that Udinese will not completely abandon their successful buying and selling strategy, but changes to the TV rights in Italy, allied with their modernised stadium should add a few more strings to their bow. In the short-term, they can hope to further enhance their financial status by qualifying for the Champions League. What a present that would be for their respected owner, Giampaolo Pozzo, who celebrates his 70th birthday next week after 25 years at the club.

******************************************************************************

The Swiss Ramble has been nominated for two awards by the EPL Talk website. If you would like to vote, please click on the following links: EPL Best Blog and EPL Best Blogger. Thanks. Voting closes Sunday 22nd May.