Rabu, 18 Juli 2012

Paris Saint-Germain - Dream Into Action

Selasa, 10 Mei 2011

Lille's French Revolution

Although Lille’s faltering form in recent weeks has caused a few to doubt their ability to sustain their sparkling challenge in Ligue 1, this weekend’s victory over Nancy restored a four point lead at the top of the table. With just four games remaining until the end of the season, Les Dogues are well on course to win their first French title since 1954.

Even though this should not be too unexpected, given that Lille finished last season in fourth place (and were the league’s leading scorers), it is still somewhat of a surprise to see a small provincial side ahead of traditional powerhouses like Marseille and Lyon. Indeed, Lille are actually chasing a domestic double, as they face Paris Saint-Germain in the French Cup Final next Saturday at the Stade de France.

Their success has been built on an impressive attacking style of play, which once again has the Northern side leading the scoring charts, with the African combination of the powerful Moussa Sow and the pacy Gervinho netting 35 goals between them so far this season. The splendidly dreadlocked Gervinho made a distinct impression for the Ivory Coast at the World Cup in South Africa, but the Senegalese Sow has been transformed since arriving on a free transfer from Rennes last summer.

The hub of Lille’s progressive formation is comprised of a trio of diminutive midfielders, like a less lauded version of Barcelona, featuring French internationals, Rio Mavuba (the club captain) and Yohan Cabaye, plus the experienced Florent Balmont.

"Gervinho - more than a haircut"

However, the undoubted star of the show is the young Belgian winger Eden Hazard, who has been named Ligue 1’s most exciting young player in each of the last two seasons, and is being chased by virtually all of Europe’s leading clubs, as well as most French defences. This young man, as Ray Wilkins would inevitably describe him, has got the lot: speed, dribbling skills, a powerful shot and the ability to create chances. One of Lille’s youth coaches did not want to go overboard in his praise, but could not resist a stirring comparison: “You have to keep perspective, as he is still very young, but he is like Lionel Messi.”

Lille’s development in the last couple of seasons is all the more remarkable, as it follows the departure of the inspirational Claude Puel, the coach who had transformed them into a truly competitive team, twice guiding unfashionable Lille to qualification for the Champions League during his six-year tenure. When Puel, a protégé of Arsène Wenger, left for champions Lyon in 2008, this could have been a hammer blow to Lille’s prospects, but instead the relatively inexperienced Rudi Garcia, recruited from Le Mans, has maintained the progress.

Famed for his ability to get results on a limited budget, Garcia has added an extra dimension to Puel’s pragmatic, hard-working side, as he let loose the attacking instincts of Les Dogues of war, resulting in Lille twice qualifying for the Europa League and potentially going one step better this season.

"Give yourself a round of applause, Michel"

Nevertheless, the principal driving force behind Lille’s ascent to the top is president Michel Seydoux, a French businessman and film producer, who became the club’s majority shareholder in 2004. Although Lille attained a startling second place in his first full season as president in 2004/05, Seydoux’s approach is the polar opposite of those owners who demand short-term success. He has not been a benefactor in the traditional football club sense of pumping in vast sums of cash and demanding instant results, but has followed the sound business principles of establishing a strategy (“to challenge Lyon in 2012”) with achievable objectives, bringing in good people to support the plan and delivering steadily improving results.

The club has adopted a long-term view, first developing a state-of-the-art training facility at the Domaine de Luchin and then working with the local authority to build a magnificent new 50,000 stadium at the Grand Stade Lille Métropole, reinforced by admirable continuity in the management team. In fact, Lille have only had two managers (Puel and Garcia) in the last nine years, a rare statistic in the uncompromising world of football.

Since Seydoux has taken control of Lille Olympique Sporting Club, often shortened to LOSC, this unheralded side has featured twice in Europe’s flagship competition, the Champions League. They qualified for the first time ever in 2005, repeating the feat the following season, when they reached the knockout stages, before being eliminated by Manchester United in controversial circumstances, as Ryan Giggs scored from a quickly taken free-kick.

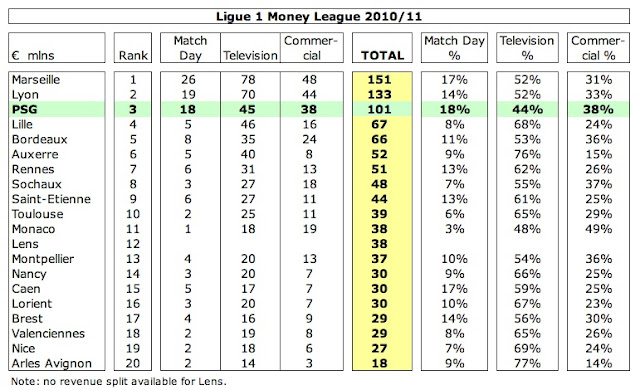

Competing at such rarified levels is heady stuff for a club with a budget as relatively low as Lille. Although on the face of it, they have little to complain about, as they sit in fifth place in the French money league with a turnover of €55 million, this is considerably less than Lyon, Marseille, Bordeaux and Paris Saint-Germain. In fact, the first two have budgets nearly three times as high (Lyon €146 million, Marseille €143 million), while Bordeaux’s revenue is twice as much. Granted, this sizeable disparity owes a lot to the Champions League money those three clubs received last year, but gate receipts and commercial income are also significantly higher than LOSC.

Given that money usually does buy success in football, as the teams with the highest turnover (and consequently wages) are most likely to win, this only makes the fact that Lille currently lead the league even more praiseworthy. To place that into context, Lens, who have almost exactly the same turnover as Lille with €52 million, are currently struggling in second to last place in the table.

Similarly, Lille are resolutely mid-table in terms of profits and losses, having reported small losses in each of the last two seasons: €1.1 million in 2009/10 and €0.3 million in 2008/09. This stability is not too bad, when you consider that the number of clubs making losses doubled from seven to fourteen last year with aggregate losses in Ligue 1 significantly rising from €24 million to €108 million, though to be fair over half of that came from just two clubs: Lyon €35 million, a big reversal from the previous year’s profit, despite reaching the semi-finals of the Champions League, and Paris Saint-Germain €22 million, continuing their series of poor financial results.

One point that stands out from the P&L league table is that Lille made more profit on player sales (€23 million) than any other French club last year, which is doubly striking, as total profits from player sales in France fell by more than 40% (€90 million) compared to 2008/09. This has been a recurring feature of Lille’s business model with the club making around €80 million from such player trading in the last four seasons. There are two ways of looking at this from a financial perspective. On the one hand, it’s a vindication of Lille’s ability to make money from developing players; on the other hand, it underlines that the club has needed to sell its prize assets in order to compensate for large operating deficits, which average €23 million over the last three seasons.

That said, the DNCG, the organisation responsible for monitoring and overseeing the accounts of football clubs in France, has stated that Lille enjoy a “healthy financial situation” despite the recurring losses at an operating level. Indeed, Lille actually reported profits three years in a row before the last two periods’ small losses (2006 €6.9 million, 2007 €5.1 million and 2008 €6.6 million), though the first two of these seasons were boosted by revenue from the Champions League.

This explains why Lille’s revenue has actually declined since its peak of €68 million in 2006 to €55 million in 2010, as the Europa League is far less lucrative than the Champions League. Like all French clubs, Lille are hugely dependent on television money and actually had the third highest reliance in France last season at 69%, only behind Auxerre and Lorient. At less than €5 million a season, gate receipts are miserably low in comparison to leading clubs in other European leagues, but that’s pretty much the norm in France with only four clubs earning more than €7 million a year, namely the usual suspects: Lyon, Marseille, Bordeaux and PSG.

Lille have done much better with TV revenue, earning €38 million, the fourth highest in Ligue 1 last season, comprising €35 million from domestic deals and €3 million from their run in the Europa League.

The domestic TV money is allocated among clubs as a mixture of fixed and variable components. The fixed element comprises 50% of the total media rights and is distributed equally among all Ligue 1 clubs, worth around €12.5 million a season, while the remainder is distributed based on league performance 30% (25% for the current season and 5% for performance over the last five seasons) and the number of times a team is broadcast 20% (15% for the current season and 5% for the last five seasons).

Although this structure is reasonably egalitarian, it does tend to favour the leading clubs, especially the broadcast element. Let’s see how this worked out for Lille last season: their fourth place was worth €11.8 million, compared to the €17.9 million received by champions Marseille. However, because clubs like Marseille and Lyon are shown on television more frequently than the provincials, Lille lose out on the notoriété with Marseille earning more than twice as much: €17.4 million compared to €7.6 million. So, in summary, last year Lille finished just three places behind Marseille in Ligue 1, but received €16.7 million less TV revenue.

However, there is a darker cloud on the horizon. The current television deal, which is worth €668 million a season, runs from 2008 to 2012, but is soon up for re-negotiation. The indications are that it will be renewed for a lower sum, as one of the existing broadcasters, Orange, has decided to withdraw from the bidding process, leaving Canal+ as the only game in town. This is potentially extremely bad news for French clubs, as only Serie A among major European leagues is more reliant on TV revenue, with Reuters estimating that the reduction may be as much as €200 million.

The French deal is currently the third most valuable in Europe, only behind the Premier League €1.2 billion and Serie A €0.9 billion, but ahead of the Bundesliga €412 million (La Liga has individual club deals). Most of the shortfall compared to the Premier League is due to overseas rights, which the English have managed to sell for an incredible 20 times as much as Ligue 1’s €30 million. Indeed, one of the suggestions made by Michel Seydoux, who has been commissioned by his peers to examine the TV issue, is for the league to spread matches over the weekend, including lunchtime kick-offs, to produce higher ratings in the emerging Asian market and address this weakness.

Of course, French clubs can boost their income by participating in the Champions League, which is what helped Lille produce what they described as “exceptional” financial results in 2006 and 2007, when they earned €21 million and €22 million respectively, not including any uplifts in sponsorships. In the latter year, this was split £18 million central TV distributions from UEFA and £4 million gate receipts. Of course, this can be a double-edged sword, as the year afterwards in 2008, Lille’s revenue plunged €24 million (or 38%).

Last year’s tournament was even more rewarding for the French representatives, who each earned an average of €25 million: Bordeaux €30 million, Lyon €29 million and Marseille €17 million. The more observant among you will have noticed that Bordeaux received more money than Lyon, even though they only reached the quarter-finals compared to Les Gones’ semi-final. This is because, as well as participation and performance payments, the clubs receive a share of the TV market pool, which is partly dependent on where a team finished the previous season in its domestic league. Therefore, apart from the natural pride at winning the championship, from the financial angle it would be better for Lille to qualify for the Champions League as winners rather than runners-up.

The Europa League is nowhere near as lucrative as its big brother with Lille €3.1 million and Toulouse €2.2 million earning peanuts (relatively speaking) for their efforts last season. Indeed, if a club battles its way through the seemingly endless series of matches to win the damn thing, it only receives the paltry sum of €6.4 million. Better than a smack in the head, but less than a club earns for simply reaching the group stages of the Champions League, even if it loses all six games.

"Moussa Sow celebrates yet another goal"

As we saw earlier, gate receipts of €4.9 million are incredibly low compared to Lille’s counterparts overseas. For example, Manchester United, the club leading the Premier League, earned €122 million match day revenue last season, which is an amazing 25 times as much as Lille. Another way of looking at this is that United generate €3.6 million a match, so they earn more in just two matches than Lille do in an entire season. Even Hamburg, from a land which is well known for its low ticket prices, earned €49 million – ten times as much.

Of course, Lille are far from unique in France in facing a tough financial challenge with their gate receipts, as amply demonstrated by another statistic: there is not a single French club in the Deloitte Money League top 20 clubs for match day revenue. The nearest are Lyon and Marseille, who both earn around €25 million, but this is still less than clubs like Valencia (19th position) and Werder Bremen (20th position), who earn about €28 million. Gate receipts in Ligue 1 have been on the low side for a while, as stadiums tend to be old, in need of renovation and have limited earnings potential, but worryingly they fell by 8% last season, though that was partly due to the impact of the recession.

Attendances have continued to fall at many clubs this season, though Lille have unsurprisingly bucked the trend following the surge towards the title with their average crowds rising an impressive 9% from 14,940 to 16,286, which represents more than 90% of the capacity of their current temporary ground, the Stadium Lille Métropole, where they moved a few years ago in anticipation of redeveloping their permanent stadium, the Stade Grimonprez-Jooris.

Instead, they have opted for the spectacular new 50,000 capacity Grande Stade Lille Métropole, which will have the highest possible 5 star UEFA rating. Featuring a retractable roof that will allow the ground to be easily converted into an indoor arena that can be used for concerts, exhibitions and other sporting events, this stadium is central to Seydoux’s ambitious plans.

The cost to Lille is limited, as the stadium is being built by the local authority, who will rent it out to the football club. However, all the revenue generated will go into Lille’s coffers, including ancillary activities such as food and beverages, merchandising and other commercial opportunities. Importantly, there will be 7,000 places for corporate hospitality, which the English clubs have demonstrated deliver significantly more bang for your buck.

"Green light for the new stadium"

Like all major investments, there is clearly an element of risk in this project, but the DNCG have no doubts that this is the way forward: “The arrival of a new stadium in 2012 will allow the club to cover its structural operating deficit and so meet its ambitious objective of balancing its books without taking into account transfers.” Assuming no Champions League revenue, that would imply an increase in revenue of €20 million, which would indeed be ambitious, but is not completely unrealistic.

There must be some concern that a leap from an 18,000 ground to a 50,000 stadium will be over-kill, but Lille would be encouraged by achieving near sell-outs in the 80,000 Stade de France, when they have moved home games there in the past, both against Lyon in Ligue 1 and for some Champions League encounters. General Manager Frédéric Paquet said, “We know it won't be easy, but we're expecting gates to average between 37,000 and 40,000,” though he recognised that this was in part dependent on Lille continuing to be successful on the pitch.

The hope for French football is that Euro 2016 will have a similarly beneficial impact on its stadiums as the 2006 World Cup had on grounds in Germany. Numerous clubs, such as Le Mans, Lyon and Le Havre, have initiated new stadium projects, while others like Marseille are looking to refurbish and redevelop their existing grounds.

Lille are also fair to middling when it comes to commercial income with their total of €12 million leaving them eighth highest in Ligue 1, though there is definitely room for improvement. As you might expect, Marseille €46 million and Lyon €43 million once again lead the way, but Bordeaux and PSG also do fairly well here, both earning around €35 million.

Even though the value of shirt sponsorship has significantly increased in France, thanks to the decision to finally allow gambling websites to advertise, the top clubs in Europe are still a long way ahead of French clubs in terms of commercial revenue with Bayern Munich €173 million and the Spanish giants, Real Madrid €151 million and Barcelona €122 million, setting the pace.

Lille’s commercial income actually fell last year from €13.8 million to €12.3 million, presumably due to the harsh economic climate, but things should improve in the future, as they announced two major deals last spring. Key shareholder Isidore Partouche’s casino operator Groupe Partouche, who have been the club’s shirt sponsor since 2003, extended their deal by five years to 2015; while Umbro replaced Canterbury, who went into administration, as the club’s kit supplier in a six-year deal.

Like most football clubs, Lille have struggled to contain their costs, even though they emphasised the importance of doing so in both the 2006 and 2007 accounts. The fact is that expenses were only just higher than revenue five years ago, but shot up as soon as the club qualified for the Champions League and have been rising ever since, even though revenue has not been growing at the same rate. In this way, while revenue rose by a respectable 55% since 2005, costs have significantly outpaced this with 160% growth.

As is always the case, the wage bill is the most important element in Lille’s costs at €49 million, which has resulted in a wages to turnover ratio of 88%, far higher than UEFA’s recommended maximum limit of 70%. Wages have been rapidly growing in the last couple of seasons from €35 million in 2008, though the revenue growth has kept the wages to turnover ratio at the same level, albeit a concerning level.

Traditionally, Lille are a low paying club, which is evidenced to some extent by the fact that they do not have one player in the list of top 20 best paid players in France, which is dominated by Lyon 7, Marseille 5, PSG 4 and Bordeaux 2. Almost unbelievably, at least to this observer, Gabriel Heinze is apparently the best paid player, followed by Yohann Gourcuff and Lucho Gonzalez.

However, Lille now find themselves in an awkward spot. As they are fifth highest in last year’s wages league, they are ahead of most other French clubs, but they are a long way behind Lyon €112 million and Marseille €92 million. In order to catch up with these behemoths and compete on a consistent basis, they will almost certainly need to spend more. As LOSC CFO Reynald Berghe put it, “The huge investment by big clubs forces small clubs to over-spend.” This is indeed what is starting to happen at Lille with the coach Rudi Garcia and five players extending contracts, including Hazard, Mavuba, defenders Mathieu Debuchy and Franck Béria, and goalkeeper Mickaël Landreau, the last of these reportedly doubling his salary.

The tax situation in France does not help either. As the tax rate is very aggressive, football clubs have to pay a higher gross salary than their competitors in other countries to ensure that the net salary is at the same level. That’s bad enough, but recently the government abolished the rule on collective image rights that had previously allowed clubs to claim an exemption on some social charges.

Another factor that potentially could adversely impact Lille is higher bonus charges, the so-called price of success, which cost Marseille €5 million last season, though general manager Paquet has claimed that the club is well equipped to handle this (whatever that means).

What is not beyond dispute is Lille’s ability to make money from player trading. Over the last decade, the club has registered net sales proceeds of €55 million, including €45 million in the last four years alone, which has been absolutely integral to their financial stability. At times, Seydoux has acted with an icy objectivity, for example in 2007 he sold all three of the previous season’s top scorers: Peter Odemwingie, Kader Keita and Mathieu Bodmer.

In many ways, they have a lot in common with Arsenal. First, the club has rarely splashed out large sums, but likes to act astutely in the transfer market. As Paquet explained, “What's important to us in signing players is not the figure, but whether it's the right price. We try to buy well and sell well. Today the biggest transfer fee we have ever paid was for Gervinho, who cost €6 million.” In addition, many players sold for big money leave their best days behind them in northern France, examples being Jean II Makoun, Keita and Bodmer, as is also the case for the north London club (Overmars, Petit, Henry, Vieira, Kolo Toure, etc).

It is impossible to discuss Lille’s transfer policy without examining their relationship with Lyon, which is questionable to some, given that Michel Seydoux’s brother Jérôme is a board member at Les Gones. As is often the case, you can look at this positively or negatively. On the one hand, Lyon have to an extent funded Lille’s progress, paying them €64 million over the last seven years for just five players: Michel Bastos €18 million, Keita €16.8 million, Makoun €14 million, Eric Abidal €8.5 million and Bodmer €6.8 million. On the other hand, it seems strange that Lille would effectively act as a feeder club to one of their principal opponents, also of course giving them their successful coach, Claude Puel.

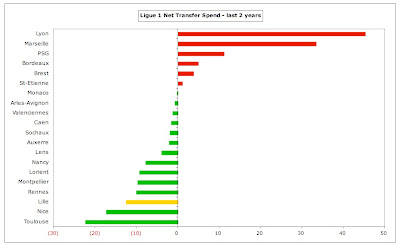

Even in the last two years, when the volume of transfers has been slashed in France, Lille have still managed to produce profits in the transfer market, mainly due to the sale of Bastos, with only Toulouse and Nice showing higher net surpluses. In stark contrast, the traditional big spenders Lyon, Marseille and PSG have continued to splash the cash. For Lille to be ahead of these clubs in the league, given their parsimonious policy, is highly commendable and a sign of excellent management and indeed coaching.

French clubs’ accounts have been badly hit by the downturn in the transfer market, as they have traditionally balanced their books by selling players. The graph below clearly highlights the magnitude of the problem, as net profits in Ligue 1 have gone down very much in line with lower profits from player sales. There’s an almost perfect correlations with net profits of €25 million dropping to a loss of €114 million, a decline of €139 million, while in the same period profits on player sales decreased from €266 million to €125 million, a decline of €141 million.

Interestingly, the vast majority of that reduction (€102 million) came from sales abroad, as Europe’s leading clubs tightened their purse strings, partly as a result of the economic conditions, partly due to the advent of UEFA’s financial fair play rules, which aim to clamp down on big spending.

This provoked the DNCG to talk of French football being in a “serious financial crisis” in their annual report even quoting Winston Churchill, “if you’re going through hell, keep going.” However, the Ligue 1 club presidents have protested that the official document paints too gloomy a picture, in particular underlining the relatively low level of debt in France compared to other European clubs, notably those in England and Spain. Of course, it’s the unrestrained spending in those leagues that has helped fund French clubs in the past, so they should not complain too much.

Any road, they do have a point, as every club in Ligue 1 has reported net assets, as opposed to the debts at clubs abroad. Lille’s balance sheet is particularly strong with no bank debt and hardly any money owed to other football clubs, resulting in total debts of €23 million, compared to assets of €47 million. That gives them a very healthy debt ratio of 48%, one of only three clubs below 50% along with Auxerre and Lyon.

In the past, clubs have used IPOs (Initial Public Offerings) to raise cash, but this seems unlikely (and unnecessary) for Lille, whose CFO Reynald Berghe said, “An IPO could be an option, but not at this point.” It’s not as if Lyon’s 2007 share offering provides an encouraging example for other French clubs, as the stock price has performed disappointingly ever since.

Having said that, the increase in payroll and higher stadium costs will weigh heavily on Lille’s finances, unless they are boosted by Champions League money. Seydoux has estimated an operating deficit of €30 million, which falls to €25 million once the €5 million transfer of Adil Rami to Valencia that was agreed in the winter is deducted, so there might be pressure to compensate in the standard LOSC manner, i.e. by selling more players.

If Hazard were to be sold, for example, his fee would cover the shortfall on its own, while the other members of Lille’s formidable attacking trident, Gervinho and Sow, might bring in another €25 million. At the moment, Lille are playing a straight bat to such questions with Seydoux arguing, “We have an ambitious policy. We see that in the biggest foreign clubs, the turnover of players each season is very light.” He claims that all the long-term deals “show the club’s ambition”, but equally this could just be a device to increase the selling price if push comes to shove.

"Adil Rami - off to Valencia at the end of the season"

Ultimately, it usually comes down to the player’s desire to stay or go. Gervinho has so far refused to sign a new deal and rumour has it that he will head off to the Premier League in the summer. Hazard is a different case, having extended his contract, but Rudi Garcia has admitted that he could still leave, but only if Lille were to receive a “super offer” for the talented young Belgian. Certainly, there would be no shortage of interest if he became available, though Hazard himself has said, “Real Madrid and Arsenal are the clubs I dreamed of joining as a child.”

Even if some of Lille’s stars were to jump ship, this would not necessarily turn out to be a disaster, as the club has proved highly adept at unearthing unpolished gems and taking them to a higher level, as happened with Sow this season. They have also begun to set their sights higher with Saint-Etienne’s French international Dimitri Payet being mentioned in dispatches as a possible replacement if Gervinho departs.

"Rudi can't fail"

However, much of Lille’s success has been built on their youth academy. As Seydoux explained, “We don't recruit the best players, but we help them grow better than others, because of the great care we bring to nurturing our youngsters.” That policy has been further strengthened by the opening four years ago of a wonderful new training ground at a cost of €20 million at Domaine de Luchin, which, according to France Football, is “more impressive than any other in Europe, including those at Arsenal, Manchester United and Barcelona.” To date, Lille have focused on local youngsters, but Paquet has also spoken of looking at working with regional academies in the future.

Lille’s commitment to youth development will stand them in good stead in the era of UEFA’s financial fair play regulations for two reasons: first, costs incurred for such activities are excluded from the break-even calculation; second, they will be able to enhance profits by later earning useful transfer fees on players developed in-house.

In fact, FFP could be beneficial to clubs like Lille, as similar rules have applied in France for 20 years, so they are very accustomed to operating within such constraints. Lille’s CFO Reynald Berghe is quietly enthusiastic about UEFA’s initiative, “It will help bring about more equality at the European level. It could be positive for French clubs.” Of course, it will also benefit those clubs who generate the most revenue, hence the desire to maximise receipts from ticket sales, which is the main driver for Lille to build a spanking new stadium.

"His name is Rio..."

That’s all future music. In the short term, Lille’s fans will understandably be concentrating on whether they can hang on to their lead at the top of one of Europe’s most competitive leagues and win their first title for 57 years. They have a tricky run-in, but proved their mettle by defeating closest challengers Marseille in the intimidating Stade Vélodrome a couple of months ago.

Lille stand on the cusp of an extraordinary achievement, namely to join Europe’s elite on a fraction of their budget. Off the pitch, they have done remarkably well to cope with a structural deficit, thanks to some skillful “wheeling and dealing” in the transfer market. It has been a triumph of long-range planning, as recognised by another football visionary, Lyon President Jean-Michel Aulas, who three years ago warned his fans, “Our next challenger as France’s biggest club will not be Marseille or Bordeaux, but Lille.” Prophetic words.

**********************************************************************************

If you like this article and others on this blog, please could you do me a favour and vote for The Swiss Ramble as Best EPL Blog and Best EPL Blogger in the EPL Talk awards? It will only take a few seconds of your time, but it would make an old man very happy. Thanks.