When Sergio Aguero crashed home the injury time winner to secure Manchester City’s Premier League title, he almost certainly gave little thought to the financial ramifications of his well taken goal, but it could be argued that this sublime moment provided the impetus for last week’s record television deal, which has climbed around 70% to £3 billion over the next three-year cycle. As the Premier League’s chief executive, Richard Scudamore, said, “We couldn’t have gone to market at a better time.”

Rabu, 20 Juni 2012

In The Premier League, The Sun Always Shines On TV

When Sergio Aguero crashed home the injury time winner to secure Manchester City’s Premier League title, he almost certainly gave little thought to the financial ramifications of his well taken goal, but it could be argued that this sublime moment provided the impetus for last week’s record television deal, which has climbed around 70% to £3 billion over the next three-year cycle. As the Premier League’s chief executive, Richard Scudamore, said, “We couldn’t have gone to market at a better time.”

Rabu, 09 Maret 2011

Is Football's Gravy Train Slowing Down?

Last month Deloitte published the latest edition of the Football Money League, their annual ranking of European clubs by revenue. Once again, the Premier League featured prominently with seven English clubs listed in the top 20, though the two highest earning clubs were still the Spanish giants, Real Madrid and Barcelona. On the face of it, this was yet another demonstration of the Premier League’s ability to generate revenue, while defying the effects of the economic recession.

Once again, Manchester United were the highest ranked English club in third position, while Arsenal, Chelsea and Liverpool all retained their positions in the top ten, though Manchester City were the biggest movers, rising nine places to 11th, one position better than Tottenham. Aston Villa were a new entry to the Money League in 20th position.

Moreover, the combined revenue of the clubs in the Premier League of around £2 billion is still miles higher than all other football leagues (Bundesliga £1.4 billion, La Liga and Serie A both £1.3 billion), though it should be pointed out that the German league is actually more profitable. On top of that, Deloitte forecast that revenue for the 2010/11 season will rise once again to £2.2 billion, thanks to the new television contract and some higher sponsorship deals.

In short, everything would appear to be rosy in the Premier League’s garden, at least from a revenue perspective. However, there have been a few indications recently that all might not be well with the Premier League’s business model with revenue growth slowing down at most clubs. Even Arsenal, who have been portrayed by UEFA as a shining example of a well-run football club, reported a 3% decline in their revenue for the first six months of 2010/11.

The signs were already there in the cycle of 2009/10 results. Revenue was flat at clubs like Everton and Sunderland, while the leading clubs have by and large also been suffering. In fact, we can reasonably take the financials of what can now be referred to as the “Sky Six” (Manchester United, Arsenal, Chelsea, Liverpool, Manchester City and Tottenham) as a decent proxy for the Premier League, as they account for almost 60% of the league’s total revenue.

In 2009/10, the revenue for these six clubs grew by 5%, which looks fairly impressive, but there are a few aspects that should be stressed. First, more than two-thirds of the £56 million increase came from just one club, Manchester City, who were boosted by a series of “friendly” commercial deals from the Middle East, while there was virtually no growth from the traditional “Big Four” clubs. Second, although revenue has risen by 77% (about £500 million) since 2004, very little of that growth has come in the last three years. This highlights the importance of the three-year TV deal with Sky, which once again climbed in 2008. Since that date, the annual percentage increase in revenue has fallen away from around 20% to 5%.

For the Premier League, there’s no doubt that television has been the gift that keeps on giving, significantly boosting all clubs’ revenue since the self-proclaimed best league in the world first held hands with Rupert Murdoch’s minions. This has almost certainly given most clubs an inflated sense of their commercial acumen, as they have conveniently forgotten the old economics proverb about a rising tide lifting all boats. Looking at how the revenue of the top six clubs has changed over the past few years, it is striking how similar their growth has been since 2004 with only a couple of exceptional events, like Arsenal moving to the Emirates Stadium or Manchester City’s new-found ability to secure marketing deals, altering the landscape.

In fact, television is now the biggest element of revenue at Premier League clubs, contributing almost half of their turnover, though the proportion is a bit lower for the top six clubs at 40%. This is much needed when you consider that match day revenue growth has effectively come to a standstill, in fact decreasing 5% in 2009/10, while commercial income barely grew at all (3%), if you exclude Manchester City. There are legitimate question marks over whether the Premier League’s growth engine will continue to motor ahead or whether it has stalled.

In order to understand what is going on, we need to explore each of the three main revenue streams at football clubs in detail: (1) Match day revenue - largely derived from gate receipts (including season tickets and memberships); (2) Broadcast revenue – largely from the Premier League and Champions League, but also including Cup competitions; (3) Commercial revenue – mainly sponsorships and merchandising.

1. Match day

Match day revenue is traditionally the most important source of revenue for football clubs, and that remains the case for our six clubs, even though it has been surpassed by broadcasting revenue. In fact, relatively high ticket prices, allied with a lot of corporate hospitality, mean that five of the top nine places in the Money League for match day revenue belong to English clubs with both Manchester United and Arsenal generating around £100 million a season.

That said, match day revenue actually declined at four of our six clubs last year (10% at Chelsea, 8% at Manchester United, 7% at Tottenham and 6% at Arsenal), while it was flat at Liverpool. This is nothing new under the sun with match day revenue hardly growing at all since 2007.

There are really only five ways to grow match day revenue: (a) raise ticket prices; (b) stage more matches; (c) increase the number of fans; (d) have a better mix of spectators (in terms of revenue generation, if not passion); (e) build a new, larger stadium. Let’s take a look at each of these factors in turn.

(a) Ticket prices. It’s difficult to see how English clubs can greatly increase ticket prices, as they are already among the highest in Europe. Even Manchester United announced a freeze in their season ticket prices this year, after the Glazers had increased prices by an average of 10% a season since their unwelcome arrival. Chelsea did raised their ticket prices at the beginning of this season, but this followed four consecutive seasons of freezing prices and was the first increase since July 2005.

"If you build it, they will come"

In a blaze of publicity, the rise in VAT also lead to the first £100 “ordinary” ticket in English football at Arsenal, and though cheaper options are available, prices are considerably higher here than, say, the £10 a head paid by most Borussia Dortmund fans.

The conclusion has to be that there is some scope for raising ticket prices, but not much. As former culture secretary Andy Burnham said, “We have seen fans priced out of going to football”, and resistance is growing towards higher prices. Last week, the Arsenal Supporters Trust warned the club that it should not attempt to cover the cost of wage increases via season ticket price increases.

(b) Number of matches. Match day revenue obviously depends on the number of games played at home, so extended runs in the cup competitions can provide a significant boost to revenue, even if the TV and prize money is inconsequential. The other side of the coin is that fewer home games can lead to a reduction in revenue, which is exactly what happened to four of our clubs. Manchester United, Arsenal and Tottenham all played fewer home ties in the domestic cups, while Chelsea were hurt by an earlier Champions League exit. Arsenal were particularly impacted as they had an incredible five fewer home matches in 2009/10 (27 compared to 32 the previous season).

(c) Number of spectators. The other aspect of volume in the economists’ price-volume equation is the number of bums on seats (“no standing, please”). Average attendances fell slightly at five of our six clubs last season, the one exception being Manchester City, whose crowds rose by over 6%. In fact, crowd levels have been remarkably resilient in this difficult recessionary climate with all of our clubs filling at least 95% of their stadium capacity. That’s a notable demonstration of support, underlined by the fact that average crowds so far in the 2010/11 season have actually marginally increased at five clubs with only Liverpool falling (the Hodgson factor?). The average attendance at Manchester United has held up, even though season ticket renewals fell 5%. Of course, the corollary of this positive news is that there is hardly any room for growth.

(d) Spectator mix. Although the “prawn sandwich brigade” is roundly derided by the majority of fans, there’s little doubt that they allow football clubs to get more bang for their buck. Perhaps the best example here is Arsenal, whose move to the Emirates brought them far more premium priced seats and notably expanded corporate hospitality facilities. In fact, Arsenal make 35% of their match day revenue from just 9,000 premium seats at the Emirates. Clearly, you don’t want too many bankers and other corporate types killing the atmosphere at the ground, but an effective balance can be struck.

(e) New stadium. Arsenal’s move to the Emirates more than doubled their match day revenue in 2006/07 from £44 million to £91 million, moving them four places up the main Money League from ninth to fifth. Sometimes, it is possible to expand the capacity of the current stadium, as Manchester United did in 2006/07, when they completed the upper quadrants at Old Trafford. However, the big money growth, especially for those clubs with smaller grounds, comes with a move to a larger, more modern stadium, which is why so many have been looking at such a possibility. However, as we have seen, there are many hurdles to overcome before successfully completing such a project.

Tottenham’s hopes of moving to the Olympic Stadium appear to have been thwarted, while Hicks and Gillett’s famous spade never quite reached the ground at Stanley Park in Liverpool. Similarly, Chelsea have struggled to find a suitable location in West London, though the Earls Court Exhibition Centre may once again be on the agenda. Manchester City’s match day income has been restricted by the deal they signed with the local council, though a new agreement means that they would get more benefit if they were to expand the capacity at the City of Manchester Stadium.

All of these factors produce vastly different match day revenues per match with Manchester United and Arsenal really coining it at around £3.5 million, while Tottenham and Manchester City earn considerably less at £1.5 million and £1 million respectively. Interestingly, Chelsea generate far more revenue (£2.4 million) than Liverpool (£1.6 million), even though their ground capacity is nearly 4,000 lower. If you ever wanted to understand why clubs are exploring other options, there’s the reason right there.

2. Television

However, in the modern world, it’s television that drives revenue growth. Its impact can be clearly seen by looking at the 45% uplift in 2008, which coincided with the introduction of the new three-year TV deal. Last season, it was the same old story with broadcasting income rising an average of just under 10% at our six clubs, increasing its share of total revenue to 40%. In fact, it’s even more important lower down the Premier League, where TV can account for a staggering 70% or more of revenue at clubs like Blackburn, Bolton and Wigan.

The Premier League can be criticised for many things, but their ability to market the “product” is beyond censure. The growth in payments secured for the TV rights has been nothing short of astonishing from the initial £253 million 5-year deal in 1992 to the £3.4 billion payment that commenced this season. To make that spectacular progress even clearer: the original deal was worth £50 million a season, while the latest brings in more than £1.1 billion.

This makes sense if you consider that audiences for live football have continued to hold up, while viewing figures have declined across the remainder of the schedule. This is premium content for pay-TV stations, whose business model relies on selling lots of subscriptions to sports channels.

Great news for football clubs, but closer examination of the new rights deals reveals an interesting (and potentially worrying) trend. Revenue for the sale of domestic TV rights (live matches and highlights) hardly grew at all in the new contract, implying that the home market may have reached saturation point. Instead, it is overseas fans that have been behind the explosive growth with the revenue doubling each time the rights are re-negotiated: 2001-04 £178 million, 2004-07 £325 million, 2007-10 £625 million and 2010-13 £1.4 billion.

Some of the increases seem barely credible: the Abu Dhabi Sports Channel paid over £200 million for the Middle East and North Africa (almost three times the £80 million paid by previous incumbent Showtime Arabia); in Singapore, an island with a population of less than 5 million people, SingTel paid £200 million to secure the rights from its rival StarHub; similarly, in Hong Kong i-Cable paid nearly £150 million, much more than the £115 million Now TV paid last time around.

As Steve McMahon, the former Liverpool player turned executive at the Singapore-based Profitable Group, said, “It is a global game. The television figures when Liverpool or Manchester United play are 600 or 700 million.” To support his assertion, the Premier League is now beamed into 575 million homes in more than 200 countries around the world.

"The future? No, very much the past"

In fact, the extraordinary globalisation of the Premier League could make English football the first world sport to earn more money from supporters abroad than at home. Foreign rights already account for 44% of the total and it would be no surprise if they overtook domestic rights in the future. Chief executive Richard Scudamore boasted, “By focusing on the quality of the game, their players and their grounds, the clubs have produced a competition that people want to watch – both at matches and at home.”

However, he who pays the piper calls the tune and there are a couple of downsides to this overseas expansion. First, it makes it more likely that kick-off times will be changed to suit fans abroad, so we can expect more lunchtime matches that can be screened during the evening peak viewing time in Asia. Second, it becomes imperative to continually promote the Premier League brand abroad, hence the unpopular proposal to play a 39th game abroad (in the same way that the NFL and NBA have marketed their product by staging matches in London) on top of the customary exhausting pre-season tours.

The other concern has to be that in the same way that revenue from the sale of domestic rights appears to have reached a plateau, this might now also be the case for foreign rights. Certainly, it would be surprising if the next deal were to double in value once again.

"Coming on tour near you soon"

Having said that, it should be acknowledged that the Premier League TV deal is still the best around, compared to other European leagues. At £1.1 billion a season, it is higher than Serie A £760 million, Ligue Un £560 million, La Liga £500 million and the Bundesliga £340 million. The difference is largely due to those foreign rights, e.g. the Premier League earns £480 million a season, while La Liga only receives £130 million and the Bundesliga a paltry £35 million.

This does not necessarily provide such a big competitive advantage to the leading English clubs, as the distribution is more equitable in the Premier League, meaning that the major Spanish and Italian clubs earned more broadcasting revenue last year. From this season, this may well change in Italy, as they have now moved to a collective agreement, leaving Spain as the only important European league where rights are sold on an individual basis.

The Premier League make great play of the fact that their distribution formula is the most equitable of all Europe’s major football leagues, citing the ratio between bottom and top clubs of just 1 to 1.7, which is considerably lower than La Liga’s 1 to 12. In 2009/10, Manchester United received the most money from the Premier League with £53 million, while bottom club Portsmouth received a very respectable £32 million. However, in La Liga, both Barcelona and Real Madrid received £117 million, while the bottom club only got £10 million. Actually, in Spain the drop starts almost immediately with third placed Valencia only receiving £35 million.

That said, there are ways in which the Premier League distribution model does favour the leading clubs. It’s true that half of the domestic money and all of the overseas rights are split evenly among the 20 clubs, but 50% of the domestic rights is not. For these funds, 25% is for merit payments, determined by the club’s final league position, and 25% is paid in facility fees, based on how often a club is shown live on television.

Each place in the league is worth an additional £800,000, which can make quite a difference, so Chelsea took the maximum £16 million last year, while Portsmouth only received £800,000. Similarly, each club is guaranteed a minimum of ten TV appearances with a maximum of 24. It’s no surprise to see that the leading clubs feature much more often than those lower down the league, so Manchester United’s £13 million facility fee was more than twice that of Hull City (£6.3 million).

Fair enough, you might think, given that more people are likely to tune in to, say, Arsenal against Spurs than Birmingham City against Blackburn Rovers. However, that does rather beg the question of whether clubs with a global fan base like Manchester United and Liverpool might start agitating for a higher share of the growing overseas rights on the same principle.

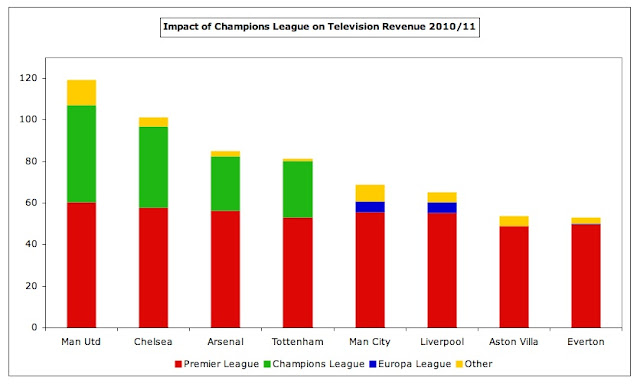

There’s certainly little difference between the leading clubs in terms of Premier League distributions at the moment with the range between first and fifth place being only £3 million (£53 million to £50 million). This only emphasises the importance of reaching the Champions League to these clubs with the four qualifiers last season benefiting by an average of £29 million each, excluding gate receipts and additional payments from sponsors.

The distributions are a mixture of participation fees (€7.1 million) and performance bonuses (in the group stage, €800,000 for each victory plus €400,000 for each draw). There are additional payments made to teams that progress further in the competition with €3 million the reward for advancing to the round of 16, €3.3 million for reaching the quarter-finals and €4.2 million for a semi-final place. The winners of the final collect a further €9 million, with €5.6 million going to the runners-up. Distributions are based in Euros, so the weakening of Sterling over the last few years has further increased the value to English clubs.

In addition, clubs receive a share of the television money from the so-called market pool. This is a variable amount, which is allocated depending on a number of factors: (a) the size/value of a country’s TV market, so the amount allocated to teams in England is more than that given to, say, Spain, as English television generates more revenue; (b) the number of representatives from a country, so an English team (with four representatives) might receive less than a German team (with only three representatives); (c) the position of a club in its domestic championship in the previous season, so if two teams from England both reach the quarter-final, the one that finished ahead of the other in the Premier League would get more money; (d) the number of matches played in the current season’s Champions League.

The size of the Champions League revenue pool has been steadily increasing, but once again the growth rate has been slowing down. Nevertheless, there is still an enormous difference between the Champions League and Europa League in terms of payments. Last season, Fulham’s valiant run to the final of the Europa League only earned them £8 million, which is £16 million lower than the smallest payment received by an English representative in the Champions League. Therefore, Liverpool’s failure to qualify for Europe’s premier competition will have a big negative impact on their finances, while Tottenham’s will receive a hefty shot in the arm.

As with any other business, however, there are threats to the Premier League’s dominance of the football television market, starting with the courts of law.

A recent non-binding opinion from an advocate at the European Court of Justice in a case brought by a Portsmouth pub landlady stated that broadcasters cannot prevent customers using cheaper foreign satellite television services to watch Premier League football. This brings into question the current model whereby the Premier League licenses its content on a country-by-country basis, which has allowed the league to fully maximise the value of its rights.

If this opinion is confirmed by a court ruling, the implication is that in the future the Premier League would have to sell the rights in one bundle to the European Union, theoretically reducing the revenue received, at least according to Omar Sheikh of Credit Suisse, “Ultimately the value of the rights will probably go down, because there are only two likely bidders on a pan-European basis.” On the other hand, a relatively low proportion of overseas income currently comes from Europe and the Premier League has to date proved very adroit at finding ways to get the most out of its TV rights.

There are other regulatory challenges to the current model. Media watchdog Ofcom has already ordered Sky to give rival broadcasters cheaper access to its exclusive rights, maybe by up to a third, which may in turn lead to Sky paying lower prices for those rights, though the Premier League (apparently linked by an umbilical cord to Sky) has decided to take legal action in an attempt to overturn the decision, as “the consequences for UK sport and UK sports fans are too serious and fundamental for us to ignore.” Yeah, right. Pull the other one, it’s got bells on.

The reality is that TV channels are not immune from the recession, as we saw when ITV Digital and Setanta went bankrupt. Although the latter’s collapse has in itself not proved problematic, as ESPN snapped up the TV rights relinquished by Setanta, if Sky were to hit financial difficulties this would be extremely serious for the Premier League and by extension the clubs. This may not seem likely, but it is not out of the realms of possibility. For example, Mediapro, the company that owns the TV rights in Spain for La Liga, applied for bankruptcy protection last year.

Although the Premier League is the current undisputed “heavyweight champion of the world” in terms of global popularity, that could change if more of football’s top stars decide to move to another league like La Liga, e.g. Cristiano Ronaldo to Real Madrid, as the “product” would then be devalued. It’s also true that to a certain extent the Premier League have had it easy so far selling its content overseas and it’s only a matter of time before the other leagues pull their fingers out and provide some meaningful competition.

"Goodbye Premier League, hello La Liga"

Perhaps the most intriguing question is how the Premier League reacts to new technology, which could be both an opportunity and a threat for the leading clubs. To date, it has responded in the traditional old economy manner by employing a company to protect its rights online and issuing lawsuits against those that provide illegal streams on the internet.

However, the emergence of fast, broadband networks might just be the catalyst for clubs to interact directly with fans. Although ventures like MUTV and Arsenal TV Online have hardly set the world alight, it is clear that foreign owners can see huge potential in online services, hence Stan Kroenke’s purchase of a 50% share in Arsenal Broadband (more than his 29.9% stake in the club). To give an idea of the size of the prize, the value of the New York Yankees’ official cable network is three times as high as the club itself.

Just because television is the medium of choice now does not mean that this will always be the case (“Video killed the radio star”) and there may well be a paradigm shift in the future in how fans watch football and how clubs generate broadcasting revenue. In the long-term, you can envisage a scenario where clubs heavily discount tickets to encourage fans to attend, as they provide much of the atmosphere and excitement that makes the Premier League such an appealing spectacle. One day they might even “invert the pyramid” and pay fans to attend…

3. Commercial

Back in today’s hard-hearted world, commercial revenue had been declining in the Premier League, but it rose an impressive 13% for our six clubs last season, though the performance was very much a mixed bag. Most of the growth came from Manchester City, whose commercial income grew a staggering 159% from £18 million to £47 million, thanks to a raft of amicable agreements with companies based in the Middle East. Manchester United have also been no slouches in the commercial arena, as their new territory specific approach delivered many new secondary partners like Turkish Airlines, Betfair, DHL, Thomas Cook, Singha and Epson. On the other hand, commercial revenue fell at both Arsenal and Liverpool.

Even with these improvements, there is still a lot of scope for growth if you compare how much revenue German clubs generate. Although this is facilitated by advertisers loving the German combination of high crowds and easily accessible televised games, it still seems strange that Schalke 04 can earn more commercial revenue (£66 million) than all but one English club. Even the £81 million generated by a fabulous franchise like Manchester United pales into insignificance relative to the £144 million produced by Bayern Munich.

That said, the leading English clubs have all managed to increase their shirt sponsorship in 2010/11, some of them significantly: Liverpool’s deal with Standard Chartered is £12.5m more than the £7.5m paid by Carlsberg; Manchester United’s deal with Aon is £6m better than the £14m from AIG; Chelsea have negotiated a £4 million increase in their Samsung deal to £14 million; while Tottenham have adopted an innovative arrangement of different shirt sponsors for league (Autonomy) and cup competitions (Investec), worth a combined £12.5 million compared to the previous £8.5 million with Mansion. In fact, the total shirt sponsorship revenue in the Premier League has now overtaken the Bundesliga.

In the same way, clubs are still managing to increase revenue from their deals with kit suppliers. There was another contractual step-up in Manchester United’s amazing Nike deal to £25 million, while Chelsea signed an eight-year extension of their deal with Adidas, which greatly increased the annual payment by £8 million from £12 million to £20 million.

Although “the boom in European football merchandising is ongoing”, according to Dr. Peter Rohlmann of PR Marketing, only two Premier League clubs make the list of top ten clubs in terms of revenue with Liverpool third and Manchester United sixth in a report compiled by Sport + Markt. However, their figures have been questioned by United, who claim that the analysis is based only on sales made at the stadium. Such figures are always debatable, as they are not always prepared on a comparable basis, e.g. if retail operations are outsourced, a club will only include a royalty payment in revenue. Nevertheless, what can be said with some confidence is that it is only really the less established leagues that can look forward to significant growth here.

The holy grail for commercial revenue seems to be selling stadium naming rights, but this has proved easier said than done for most clubs. While Chelsea have often spoken about hoping to secure £10 million per annum, the only team in our six clubs that has actually sealed a deal is Arsenal – and they needed to move to a new stadium to achieve this.

Furthermore, in order to gain funding for the stadium construction, the deal with Emirates is not particularly good (£90 million for 15 years up to 2020/21, including the shirt sponsorship until 2013/14), which has held back the club’s commercial income. Arsenal have invested in an expensive new commercial team, so we shall see whether they can deliver any growth in the short-term. As chief commercial officer Tom Fox said, “Ultimately a club is worth what it monetizes.”

That said, commercial revenue is impacted by a number of external factors: the economic climate, number of home games (merchandising and catering) and progress in cup competitions, due to performance-related clauses in sponsorship agreements.

Nevertheless, the flood of new foreign owners in the Premier League clearly believes that there is gold in them there hills. As an example, John W. Henry, whose New England Sports Ventures bought Liverpool a few months ago, spoke of the club’s global revenue potential, when outlining his team’s plans to transform the Reds’ finances, as he did with the Boston Red Sox. NESV clearly hope to use their baseball experience to generate more commercial revenue from global sources.

One other “revenue” stream for football clubs is the profit made on player sales, which you might think would be negligible for the leading clubs, but has brought in a lot of cash for Manchester United and Arsenal, who averaged £39 million and £29 million respectively over the last three years. Indeed, the main reason for the drop in Arsenal’s interim profits was the lack of player sales. Some top clubs on the continents actively use player sales as part of their business model, two obvious examples being Lyon and Porto.

"My profit on sale was how much?"

So why is revenue growth important? We can look at that from two very different perspectives.

First, English clubs need strong revenues to compete with their European rivals when trying to attract world-class players, both in terms of transfer fees and wages. This is the virtuous circle often referenced by Richard Scudamore, “The continued investment in playing talent and facilities made by the clubs is largely down to the revenue generated through the sale of our broadcast rights.” OK, he’s talking specifically about television revenue here, but the general point remains valid.

Whether this is desirable is another question, as the wages to turnover ratio is nearing a critical 70% in the Premier League. Each time that the clubs’ revenue substantially increases, usually through a more lucrative broadcasting deal, the clubs simply pass the additional funds straight into the players’ bank accounts. According to a report recently published by UEFA, although top-flight clubs across 53 countries increased their revenue by 4.8% to €11.7 billion, costs rose by nearly twice that at 9.3%, resulting in total losses of €1.2bn – more than twice the previous record.

The advent of UEFA’s Financial Fair Play regulations, which will force clubs to balance their books without relying on a benefactor’s generosity, mean that the ability of clubs to generate more revenue from football operations will become critically important. As John Henry said on his arrival at Liverpool, “With the financial fair play rules, it is really going to be revenue that drives how good you club can be in the future.”

"Richard Scudamore - nothing wrong with the Premier League"

Given their stellar showing in the Deloitte Money League, this would appear to place England’s leading clubs at a considerable advantage. Certainly, the Premier League’s “see no evil, hear no evil” chief executive, Richard Scudamore, remains confident, “People said we were a bubble going to burst. They said it eight years ago, six years ago, four years ago. From all the indicators we've got, we don't think interest is lessening.”

That is clearly the case right now, though as an industry football is very fortunate that it has such loyal “customers”. The reality is that people love football and will spend considerable sums to follow their team, be that through attending matches, watching them on television or buying the club’s merchandise – even when they disapprove of the club’s owners, as we have seen at Manchester United.

However, a few signs are emerging that the clubs will have to work harder to earn their revenue growth, become more commercial, if you will, rather than simply rely on the three-year cycle of television rights delivering ever-increasing sums of money. The time is fast approaching when they will need to seek alternatives. At that point, we shall see whether football clubs do indeed have the skills to pay the bills.