After the disappointment of losing to Swansea City in the 2011 Championship play-off final, not many people would have expected Reading to bounce back so well that they not only secured promotion to the Premier League last season, but they went up as champions, ahead of more fancied clubs like Southampton and West Ham. Their thoroughly likeable manager, Brian McDermott, deserves a huge amount of credit for superbly marshalling his resources, especially after losing leading scorer Shane Long to West Brom and skipper Matt Mills to big spending Leicester City in the summer.

On paper, Reading’s team featured few stars, making the incredible run of form after Christmas that took them to the title even more impressive. Their top scorer, Adam le Fondre, netted just 12 goals after being picked up pre-season for the princely sum of £350,000 from Rotherham United. No other player reached double figures, though Reading played some entertaining football, especially the two wingers, captain Jobi McAnuff and the Malian Jimmy Kébé.

The Royals’ success was built on the tightest defence in the division, including player of the season Alex Pearce, the experienced Latvian colossus Kaspars Gorkšs and the veteran Irish full-back Ian Harte. Behind that uncompromising combination, the Australian goalkeeper Adam Federici again demonstrated his international class.

"Pearce - Come on, Alex. You can do it!"

Despite being one of the oldest clubs in the Football League, this is only the second time that Reading have reached the top flight. Steve Coppell’s team was the first to achieve this honour, finishing in a remarkable eighth place in the Premier League in 2006/07, just missing out on European qualification. Unfortunately, their stay was brief, as the dreaded second season syndrome led to relegation the following year. They very nearly made an immediate return, but finally lost to Burnley in the play-offs, leading to the departure of key players like Kevin Doyle and Stephen Hunt and Coppell’s resignation.

His replacement, Brendan Rogers, lasted just six months, before leaving the club “by mutual consent” in December 2009, when McDermott was given his chance. The former Arsenal striker, who had been at the club since 2000, initially as chief scout, then the under-19s and reserve team manager, seized the opportunity with both hands.

In his first season, he took the club out of the relegation zone into a creditable ninth position and followed this up with an encouraging fifth place in 2010/11, before this year’s triumph. McDermott also guided Reading to two FA Cup quarter-finals in that period, overcoming many Premier League clubs on the way, including a memorable victory over Liverpool at Anfield.

All in all, their ebullient chairman, Sir John Madejski, was fully justified in his claim that this was “the most successful period in the club’s history.” Much of this is down to his own skill in patiently pushing the club forward, not least the 1998 move to the modern stadium that bears his own name, affectionately know as the “Mad Stad”.

"McDermott - the life of Brian"

As well as the advancement to the promised land of the Premier League, there are also ch-ch-ch-ch-changes off the pitch with the announcement of a takeover by the Russian Anton Zingarevich, who bought the club for £25 million through Thames Sports Investment (TSI) last month. Madejski has been effusive in his praise of the 29-year-old businessman, “This fit is so good it is not funny. Not only does Anton come from a very wealthy family, but he was also educated in the area.”

Details of the deal are still sketchy, but it has been reported that TSI has bought 51% of the club immediately for £12.7 million with an obligation to purchase the remaining 49% for a further £12.3 million by 30 September 2013. Continuity should be assured by Madejski remaining as chairman until at least 2014 with an invitation to become Life President if he decides to step down.

Madejski will be a tough act to follow. He has been chairman for over 20 years after buying the club in 1991, taking it from the brink of receivership and reviving the club’s fortunes. His commitment has been admirable, especially as he is not really a football man, once claiming, “I know squat about football.” Indeed, after relegation from the Premier League, he said that he would be “horrified rather than surprised” if he were to still be in charge in five years time.

Although a wealthy man by most people’s standards, having made serious money from selling Auto Trader magazine, he cannot compete with the big hitters at the highest level, “Football is really for the super rich. It is a rich man’s foible.” Furthermore, his companies have been badly hit by the recession, especially the collapse of the property market that necessitated the renegotiation of bank loans at Sackville Properties.

"Madejski - Johnny Was"

In truth, he has been willing to sell for a while. As far back as 2007, he said, “If there's some billionaire out there who thinks he could take the club to the next level, while respecting what it's is all about, then I'd be happy to pass on the baton.” However, although it was important that any buyers had “enormously deep pockets”, they had to be the right type of bidder, “'I've spent 20 years building this up and I'm not just going to sell it to some asset stripper or some consortium that will fall out and sell it all off in bits”, which gives some encouragement to sceptical supporters.

That said, there are inevitably concerns regarding any takeover, especially as there was a lengthy delay before TSI was allowed to complete the acquisition. Specifically, the football authorities were worried about exactly who was behind the investment and wanted to see proof of funds.

The real money in the Zingarevich family is with Anton’s father Boris, who is the founder of Ilim Pulp, a timber and paper business, and is the largest shareholder in Enerl, a New York based power company. Unhappy comparisons were drawn with Portsmouth, whose trail of woe included allegations that one-time owner Sacha Gaydamak was a mere front for his much richer father.

In addition, little was known about Chris Samuelson, the main TSI representative, beyond the fact that he was a director of Mutual Trust SA, a financial services firm based in Switzerland specialising in incorporating discreet investment vehicles in offshore jurisdictions. In such circumstances, it is natural that questions will be asked about whether the purchaser is “fit and proper”, particularly as the Zingarevich family pulled out of a bid to buy Everton in 2004 at the last minute. This time round, Samuelson assured fans that the deal would go ahead, “There’s no problem with the money. It will be a cash deal, not loans and not leveraged finance.”

"Just can't get McAnuff"

The acquisition was finally announced by Reading on 29 May in a statement that confirmed that it complied with all Premier League and Football League requirements. In fairness, the delay might simply be due to Reading’s promotion, which meant that both leagues wanted to review the transaction.

Madejski seems to have no doubts about the new kids in town, “I have no misgivings about their credentials or integrity. Anton ticks all the boxes and we’re lucky to have him.” Such a vote of confidence from a man as honourable as Madejski is heartening, though only time will tell whether Zingarevich merits this positive reference.

It is not known how much money Zingarevich has, though the Daily Mail reported that his family was worth £460 million. If that is correct, it would be interesting, because that would be a long way short of the billionaire that Madejski has been seeking for so long.

One thing that is not in doubt is their good timing, as they agreed to buy Reading at a very good price just before promotion to the far more lucrative Premier League was secured. As Madejski admitted, “The club is more valuable now, but I have struck a deal, and a deal is a deal.”

"Kaspars the friendly ghost"

In any case, although TSI have promised some financial support, Reading fans will be disappointed if they expect another Roman Abramovich. The new strategy is likely to be much the same as the business-like approach operated by the club in the past few years, albeit with a little “more fiscal help”, partly financed by the new owners, partly by the greater riches available in the Premier League. Madejski advised, “They’re not going to go at it like a bull in a china shop. It’s going to be done in a prudent, sensible way – the Reading way.”

That’s a reference to Reading’s two-pronged policy of ensuring the club’s financial stability, while still trying to give themselves a reasonable chance of achieving success on the pitch. In the past, Madejski has been unapologetic about focusing on long-term viability, as opposed to short-term gratification: “We will not gamble with our future, as some clubs in our position have done at great cost. Instead, we are attempting to develop a club with a strong infrastructure that is built on solid foundations.”

Although some fans have criticised the chairman for a perceived lack of ambition and reluctance to invest more in the squad, Madejski can point to the team’s successful record on the pitch in the past few seasons that “demonstrate we can run the club in a prudent manner, but still achieve historic results.” Indeed, the 11 best seasons in Reading’s history have all come under the stewardship of his board. Maybe even more could have been accomplished with more investment, but money is no guarantee of success.

Since Reading’s relegation from the Premier League in 2008, they have effectively been a selling club with net sales of £32 million in the transfer market (purchases £12 million, sales £44 million), a complete turnaround from the previous five years which had an aggregate net spend of £18 million. Even then, they were hardly the biggest spenders around, as seen by their record buy being just £2.5 million to secure the services of Emerse Faé from Nantes in 2007.

They have become masters at buying low and selling high, signing players for peanuts, but obtaining large fees for them in each of the last four years: 2008/09 Dave Kitson (Stoke City) £5.5 million, Nicky Shorey (Aston Villa) £3.5 million, Ibrahima Sonko (Stoke City) £2 million; 2009/10 Kevin Doyle (Wolves) £6.5 million, Stephen Hunt (Hull City) £3.5 million; 2010/11 Gylfi Sigurdsson (Hoffenheim) £6.5 million; 2011/12 Matt Mills (Leicester) £4.5 million, Shane Long (West Brom) £4.5 million plus add-ons. As most transfer fees are not disclosed, we have to exercise a degree of caution here with Madejski warning, “The sums of money broadcast in the media are nothing like the actual figures.”

Nevertheless, it is evident that selling players has been an important part of Reading’s strategy. As the 2011 annual report stated, “Player sales remained necessary to allow us to continue to run a competitive squad.” That may seem like a classic oxymoron, but it does make sense to the extent that the sale of one or two specific players for reasonably big money has financed the wage bill of those remaining.

In the last four years, only three Championship clubs (Portsmouth, West Ham and Middlesbrough) spent less than Reading on transfers, though to be fair very few have splashed the cash with only ten clubs out of 24 reporting net spend. In fact, only three clubs (Leicester City, Hull City and Nottingham Forest) have spent more than £10 million (net) in that period and none of these has set the world alight.

It should also be noted that those with high net sales have been badly impacted by relegation from the Premier League. This is partly due to lower revenue, but is also down to some players wanting to move to play at a higher level, as was the case with Shane Long. Madejski explained, “The reason he left is he’s a Premier League player. Had we got promoted, he would be playing for Reading.”

That has not stopped some of the crowd urging Madejski to “spend some money”, though in rather more forceful terms, but to a degree Reading managers have become victims of their own success here. McDermott’s title winning side was built on a relative pittance, while in the past Madejski praised Steve Coppell for achieving “the minor miracle of obtaining such excellent results without having to invest huge sums in the transfer market.”

This thrifty stance has been reflected in Reading reporting profits in four out of the last five years, a rare feat in the cutthroat world of football. Very good profits of £13 million were made in the two Premier League seasons (£6.6 million in 2007 and £6.7 million in 2008), but this was largely used to invest in infrastructure and offset previous losses. These added up to £12 million in the two seasons before promotion, including a £6.5 million loss in 2006, when “the board made a conscious decision to invest heavily and push for promotion”, resulting in a record points total.

Following relegation, Reading still managed to make money in the seasons benefiting from parachute payments (£3.1 million in 2009 and £1.4 million in 2010), even though they admitted that in the first season they “went for broke and over-spent on the budget.” This can be seen by the wage bill in 2009 being twice as much as the last time they had been in the Championship just three years earlier, leading to a hefty operating loss of £12.5 million, only financed by substantial profits on player sales of £16.3 million.

This could not last, so the (football) wage bill was trimmed by 30% from £25.5 million to £18.1 million in 2010, reducing the operating loss to £2 million. Madejski noted, “People have to recognise that football is a business and you have to cut the coat according to the cloth. And if the cloth isn't there, it isn't there. Times are hard and we have to live within budgets.” This is particularly pertinent for Reading, whose revenue from football activities has fallen by around two-thirds from £52 million in the Premier League to £17 million last season in the Championship.

"Harte and soul"

Despite the focus on the financials, Reading made a loss of £5.4 million in 2011, which was £6.8 million worse than the 2010 profit of £1.4 million. In some ways, this is a good achievement, as they had to cope with the loss of a £12 million parachute payment, slightly offset by additional income from the play-off final. In spite of this hefty revenue reduction, costs remained at the same level, with the shortfall reduced by profits on player sales of £5.8 million.

In cash terms, this funded the £5.8 million loss (EBITDA – Earnings Before Interest, Taxation, Depreciation and Amortisation). In other words, the 2011 deficit was effectively attributable to non-cash, accounting items, namely depreciation on fixed assets and player amortisation (the annual expense of writing down transfer fees). That effectively left no money to spend. As Madejski put it, “If you look at our figures, you will see that keeping the show on the road, with all the expenses involved in football, you will see there's no heap of cash waiting to be spent.”

At this point, we should clarify Reading’s corporate structure. The profit and loss figures are from The Reading Football Club (Holdings) PLC, which is the parent company of The Reading Football Club Limited, which itself has two wholly owned subsidiaries, the Madejski Stadium Hotel Limited and the Reading FC Community Trust.

Revenue is boosted by the non-football activities with the hotel contributing £5.2 million and the Trust £0.7 million, leaving the pure football revenue as £17.2 million. Although the hotel was intended to provide a diversified revenue stream, it has been impacted by the poor economic climate and local competition, so has not yet delivered the goods, though it does generate some cash once depreciation is added back.

The important point to note is that these other activities make very little difference to the club’s bottom line, e.g. in 2011 the football club was responsible for £5.0 million of the total loss of £5.4 million for the holding company. Excluding interest payments, the hotel made a loss of £185,000, while the Trust reported a small profit of £29,000.

Of course, the vast majority of clubs in the Championship lose money with only three of the 24 contenders making money in 2010/11: Watford (and they would have reported a loss without a £13 million “inter-company debt waiver”), Scunthorpe United and Leeds United, and nine losing more than £10 million. This is partly a result of low TV money in England’s second tier, but also due to many clubs over-spending in order to reach the Premier League.

Reading’s £5.4 million loss places them in the top half of the profit table, but their record over time is one of the best in the Championship. To place it into perspective, another team that plays in blue and white hoped shirts, Queens Park Rangers, lost a massive £58 million in the three seasons before promotion, while Reading virtually broke even in the same period.

That said, there is little doubt that this has been achieved on the back of player sales. Excluding profit from player sales of £26 million between 2009 and 2011, Reading’s loss would have been £27 million.

For example, in 2009 the club reported a profit before tax of £3.1 million, but this would have been a £13.2 million loss without player sales. As the club explained in the 2009 annual report, “At the end of the financial year, we had to begin recouping the season’s losses”, hence the sale of Kevin Doyle on 30 June (the last day of the financial year). Matters were complicated that year, as the club also had to repay a £7.5 million overdraft on top of the £6.3 million cash loss (EBITDA £(5.5) million plus interest payments of £0.7 million), leading to even more sales than usual.

It was a similar story in 2011, when the reported loss of £5.4 million would have been £11.1 million without player sales, as Madejski explained, “Our budget was set with the intention of supporting the costs of the playing squad through player trading and we did so primarily with the sale of Gylfi Sigurdsson.” More of the same can be expected in 2012, as the money made from the sale of Mills and Long will (partly) compensate the almost inevitable operating loss.

Although many might consider Reading a “small” club, despite their recent progress, their revenue is actually not too bad at all. If we exclude the £15 million of parachute payments received by Burnley, Middlesbrough and Hull City, only five clubs generated more than Reading’s £17.2 million (from football activities) in 2010/11. Leeds United (£33 million) and Norwich City (£23 million) were a fair way ahead, but the other three clubs earned about the same as Reading: Derby County £18.1 million, Leicester City £18.4 million and Ipswich Town £17.2 million.

Incidentally, two of the clubs promoted to the top tier in 2010/11 had even lower turnover: QPR £16.2 million and Swansea City £11.7 million, so maybe Reading’s elevation this season should not come as too great a surprise.

Of course, the major problem for Reading has been the declining revenue, which has fallen by £35 million from £52 million in the Premier League in 2008 to £17 million in the Championship in 2011. The majority of that (£26 million) hit them immediately in 2009 with the remainder coming two years later after the parachute payments ran out.

Clearly, the primary driver of the revenue decrease is television (falling from £34 million to £6 million), but the other revenue streams have also been adversely affected with match day income dropping from £11 million to £7 million and commercial revenue reducing from £7 million to £4 million.

The influence of television on a football club’s finances is undeniable and Reading are no exception. Relegation from the Premier League in 2007/08 led to an instant £19 million decrease with TV revenue falling from £33.7 million to £14.6 million, even though the fall was cushioned by annual parachute payments of around £12 million for the next two seasons.

When these stopped in 2010/11, the TV money slumped to £6.1 million. This mainly comprised the distributions made to all clubs in the Championship of £5.2 million, made up of a £2.5 million central distribution, a £2.2 million solidarity payment from the Premier League (up from £1.3 million the previous season) plus an additional £0.5 million as their share of the parachute payments for Newcastle and WBA, because they went straight back up to the top tier. The remaining TV money is for live broadcasts and progress in the cup competitions.

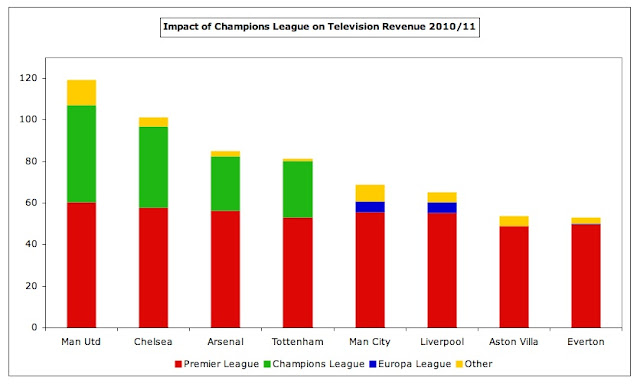

TV revenue in 2011/12 will be around the same level, but will shoot up next season, as each club in the Premier League receives around £40 million. The distribution methodology is fairly equitable with the top club (Manchester City) receiving around £61 million, while the bottom club (Wolves) gets £39 million. The lion’s share of the money is allocated equally to each club, which means 50% of the domestic rights (£13.8 million in 2011/12) and 100% of the overseas rights (£18.8 million). However, merit payments (25% of domestic rights) are worth £757,000 per place in the league table and facility fees (25% of domestic rights) depend on how many times each club is broadcast live.

Promotion is often seen as being worth an additional £90 million, which is a little misleading, as it is not all received in one fell swoop. It works like this: even if Reading do come straight back down, they would receive £40 million TV income plus £48 million parachute payments over the next four years (£16 million in each of the first two years, and £8 million in each of years three and four) plus additional gate receipts and better commercial deals. Of course, that calculation conveniently ignores the £5-6 million TV revenue already received in the Championship, but it’s still a magnificent prize.

The other point is that the club will surely eat into that higher revenue by increasing wages and other costs. As Madejski said, “It’s all very well getting to the Premier League, but you need deep investment to stay there.” Nevertheless, the net effect is still likely to be positive, as we can see from examining the three teams that were promoted to the Premier League in 2009/10. Newcastle United, WBA and Blackpool, all dramatically improved their operating profitability, even though wages increased.

Based on the match day income and commercial income received the last time Reading were in the Premier League, they can anticipate total revenue of around £58 million, which might seem like a huge sum after the £17 million in the Championship, but it is still relatively low for the top tier, e.g. only Blackpool and Wigan Athletic generated less revenue last season. For some context, Manchester United’s £331 million is more than five times their budget.

The recently announced three-year domestic TV deal starting in 2013/14 only emphasises the vast financial gulf between the two top divisions. Assuming a reasonable increase in the overseas deal, Premier League clubs can expect at least £20 million additional revenue a season. That makes it even more imperative to survive in the Premier League, especially as the Football League TV deal that kicks off in the 2012/13 season is actually 26% lower than the current contract.

Match day income of £7.3 million is pretty good for the Championship, though clubs like Manchester United and Arsenal generate as much as Reading achieve in a whole season in just two games. In fairness, in 2010/11 only Leeds United earned more revenue per fan (of the 10 Championship clubs with the highest attendances), as Reading took in more revenue than many clubs with higher crowds.

in last season’s promotion campaign, attendances climbed 9% to 19,219, the ninth highest in the Championship, though this was still some way short of the near 24,000 crowds achieved in the two Premier League seasons.

Having reduced ticket prices following relegation, Reading have hiked prices for next season with season tickets going up by 33% (though prices were frozen for those taking advantage of the early bird offer). Although many clubs have tried to beat the recession by keeping prices at the same level (or even reducing prices in the case of Wigan, West Brom and Sunderland), the increase for a promoted club is perfectly understandable and has not dented season ticket sales, which are approaching the 18,000 maximum.

In 1998 Reading moved from Elm Park to the Madejski Stadium, which is shared with the London Irish rugby union side, enjoying much support from the local council. It cost around £40 million, though this was partially offset by selling land from the old ground and around the new site. With a capacity just over 24,000, it is not particularly large for a Premier League club, though they have planning permission to extend to 38,000 and Zingarevich has promised, “If we stay up in the first year, then we will upgrade the stadium.”

The Royals will be looking to increase their commercial income in the Premier League from the £3.8 million in 2010/11. Even that includes £0.6 million commission from rugby matches, so there is plenty of room for improvement.

The current shirt sponsor is Waitrose, who have extended their deal to 2013, having replaced Kyocera in 2008. Financial details have not been divulged, though reported estimates include “a significant six-figure annual sum” and £1.5 million from various marketing publications, so we could assume an average of £1 million. This would be towards the lower end of Premier League deals and obviously significantly behind the £20 million deals for the leading clubs. Reading also have a long-term kit supplier deal with Puma that runs until 2013.

Those that argue that Reading have shown no ambition might be given pause for thought when they see a wages to turnover ratio of 106% in 2010/11. To place that into context, that’s nearly as much as big spending Manchester City’s 114%. Reading’s ratio deteriorated from the previous season’s 66%, as they held the wage bill at the same level, despite revenue plummeting more than £10 million after the parachute payment stopped. In fact, the wage cut of 41% (£13 million) since relegation is much less than the 67% (£34 million) revenue decline.

In fairness, nearly half the Championship clubs have a wages to turnover ratio over 100%, but Reading’s wage bill of £18.3 million is one of the most competitive in the division (sixth highest) and much the same as Norwich and Swansea (two of the promoted clubs that season). It may be even higher in 2011/12, assuming that bonuses were paid for winning the league.

However, it was still a lot lower than every Premier League club in 2010/11 with the exception of Blackpool, so is likely to shoot up in 2012/13. This will be one of Reading’s major challenges following promotion. As Madejski said, “Footballers are paid an extraordinary amount of money – that’s why football is struggling. I have been in the game for nearly 20 years as a chairman and all I’ve seen is this inextricable rise in players’ wages, which is where it all goes wrong.” Indeed, there has already been talk of signing Russian striker Pavel Pogrebnyak on £30,000 a week, which would make him the highest paid player in Reading’s history.

Note that the total wage bill at Reading was £20.5 million, including wages for the hotel and other companies, but that would not be a fair comparison with other teams, so I have used wages for the football club only.

Excluding salaries and amortisation, Other Costs for the football club are £5.7 million. Comparing that with other Championship clubs with high revenue (not benefiting from parachute payments), we can see that this is on the low side with Leeds, Leicester, QPR and Derby spending almost twice as much in this area.

Reading have reduced their debt from £45 million to £35 million in the last two years, mainly due to the repayment of a £7.5 million overdraft. The club has been hugely reliant on the chairman’s support, in the form of £26.3 million loans (up £0.5 million in 2011) at low interest rates. These comprise £17.1 million interest-free for the hotel and £9.2 million for the football club at 1% below the HSBC Bank base rate. Furthermore, £2.3 million of interest has merely been accrued, so not actually paid. In fact, Madejski has “never taken any money out of the club”, meaning nothing for directors’ fees or dividends either, only collecting £18,000 annual rent for the training ground.

Thanks to Madejski’s support, the remainder of the debt is fairly small, made up of £7.1 million bank loans and £1.4 million other loans (from Scottish and Newcastle PLC and Close Leasing Limited). Reading’s status here should not be under-estimated, given the situation at other clubs, as the Football League chairman, Greg Clarke said, “Debt's the biggest problem. If I had to list the 10 things about football that keep me awake at night, it would be debt one to 10. The level of debt is absolutely unsustainable.”

In fact, as Chris Samuelson from TSI said, “Reading is one of the few football clubs with a strong balance sheet” with net assets of £3.6 million. Although this is £5.4 million lower than the prior year, after the 2011 loss, in reality it is under-stated, as player values only have an accounting value of £3.2 million, while they are worth much more in the real world (£15.5 million per Transfermarkt).

In addition, liabilities include an £11.7 million deferred contribution from Salmon Harvester Properties Limited, the company that bought Elm Park, where the cash has been paid, leaving annual contributions released to the profit and loss account over the stadium’s expected life. The stadium is valued at £30 million, while the hotel is £23 million (no value for the training ground, as this is owned by Madejski).

In the last six years, the club has produced operating cash flow of £15.5 million, but £21.4 million was spent on infrastructure (hotel extension, conference centre, new pitch, training ground) and £3.2 million on interest payments, leaving a shortfall of around £10 million. This has been financed by player sales of £6.1 million and £8 million of new loans.

In the Premier League years, more cash was available, but it was “reinvested into the playing squad – particularly on player wages – and the infrastructure”, so there was no great surplus. After relegation in 2009 there is a clear switch to: (a) generating cash from player sales; (b) spending less on infrastructure. The loan repayment has also reduced interest payments from £0.6 million to £0.2 million.

Looking ahead, Reading’s top priority will obviously be Premier League survival. This will be a tough ask, especially as few players have experience in the top flight, but captain Jobi McAnuff said that they could draw inspiration from Norwich and Swansea, who did well enough with pretty much the same squads.

"Kébé - Jimmy, Jimmy"

That said, we can expect some loosening of the purse strings from the new owners, reinforced by the extra revenue from the Premier League, though they are unlikely to break the bank, as Madejski explained, “What I don’t want is people thinking Reading are an open cheque book. We will be as careful as we have been in the past. There will be a possibility to strengthen, but only in a sensible way.”

In this way, limited funding was made available in the January transfer window to bring in Jason Roberts, which was not much, but made a big difference. There has been press speculation that McDermott will be given a transfer kitty of £15 million this summer, but perhaps the most important point is that the club will now be able to retain its best players, which is a “hugely important step” according to the manager.

TSI have also spoken of their desire to continue focusing on the scouting network and the academy, which has been very successful in producing home grown talent, such as Alex Pearce and Simon Church, while developing the likes of Jem Karacan. Madejski has invested a lot in this area, including upgrading the training facilities. He also hired Nicky Hammond in 2003 as the club’s first director of football, a “very important” role according to McDermott. It is not clear how this will be affected by the introduction of the Elite Player Performance Plan (EPPP), though this is likely to hurt Reading’s ability to sell young stars to top clubs for large sums.

"Zingarevich - the Russians are coming"

If Reading are relegated, they will be confronted by the new Financial Fair Play (FFP) framework, which was approved by the Championship clubs in February. That will see the introduction of a breakeven model, requiring clubs to stay within pre-defined limits on losses, though that should not be too problematic for a club with their prudent philosophy.

Reading’s progress on the pitch, while keeping a tight hold on their finances, is encouraging to those who despair of the massive amounts of money thrown away in football. They have bucked the trend of buying success by adopting a sensible, long-term plan – that has worked.

Although there are still many questions about the new owners, there is no doubt that Madejski has handed over a club in excellent shape. Reading have much potential with a modern stadium located in the Thames Valley, one of the most affluent parts of the country, with little competition from neighbouring clubs. As Sir John said, “It is the end of one era, but the start of another.” His hope that this will “take Reading on to a different level and into Europe and beyond” might be a little optimistic, but only time will tell.