Over the years, there have been many reasons for football fans to admire Fiorentina, not least the myriad midfield talents of such creative stars as Giancarlo Antognoni, Roberto Baggio and Manuel Rui Costa and the goalscoring prowess of the prolific Gabriel Batistuta. Others have been attracted to the romance of following a club from Florence, one of the most beautiful cities in the world, while fashion gurus have simply appreciated the distinctive purple of the team’s shirts, which inspired the club’s Viola nickname.

Whatever the supporters’ motives, the current season has so far not been one to remember, especially the disastrous start that left Fiorentina rock bottom of Serie A after seven games with just five points. Since those dark days, there has been a recovery of sorts and a run of 14 games with only one defeat means that the team has climbed into the top half of the table.

This should be the least of the Viola’s aspirations, as they managed to retain most of their key players last summer, despite overtures from many “larger” teams for their stars, like their Italian internationals, playmaker Riccardo Montolivo (Juventus) and striker Alberto Gilardino (Napoli), Peruvian winger Juan Manuel Vargas (Real Madrid) and veteran French Goalkeeper Sebastien Frey (Arsenal).

"Juan Manuel Vargas - El Loco"

In fairness, they have suffered from a lengthy injury list, including (among others) the exciting young Monetenegrin forward Stevan Jovetic, summer signings Gaetano D’Agostino and Felipe, the wonderful Montolivo and the penetrative Vargas. Recently, the curse also struck Valon Behrami just weeks after the Swiss midfielder was acquired from West Ham in the January transfer window.

Added to that was the long-term absence of Adrian Mutu, due to a nine-month ban under Italy’s anti-doping laws for taking an appetite suppressant. Although the Romanian’s appetite for (self) destruction apparently knows no bounds, Fiorentina have badly missed his goals, leaving them over-reliant on Gilardino.

However, perhaps the main reason for Fiorentina’s shaky start to the season was the departure of their widely admired, long-serving coach, Cesare Prandelli, to take charge of the Italian national team. He was replaced by Sinisa Mihajlovic, who has vast experience of Italy as a player, but relatively little as a coach, though he did pull off a minor miracle last season when he steered Catania to safety from relegation. Nevertheless, Prandelli was always going to be a hard act to follow, especially for such a young coach.

"Alberto Gilardino - scoring machine"

In the midst of all this upheaval, one fact has almost gone unnoticed, namely that Fiorentina are currently the most profitable club in Serie A, based on a survey published by La Gazzetta dello Sport a couple of weeks ago. This achievement is all the more remarkable, given the club’s recent turbulent financial history, which included Fiorentina falling into administration in 2002. This followed a period of serious mismanagement by the club’s owner, Vittorio Cecchi Gori, who had taken over from his father, Mario Cecchi Gori, in 1993, after the death of the famous film producer.

Mario was much loved by the Fiorentina tifosi, but his son was a different kettle of fish. He angered the fans by sacking the successful coach Gigi Radice, after the latter made some off-colour remarks about the owner’s actress wife, replacing him with Aldo Agroppi, whose short-lived reign turned out to be a complete disaster, culminating in the club’s relegation to Serie B. At this point, the scale of Fiorentina’s financial problems became all too clear, following years of lavish spending on transfers and salaries, which resulted in massive debts and the club failing to pay its players.

"Della Valle waves goodbye to the presidency"

As a result of the financial collapse, the football authorities relegated Fiorentina two more divisions to Serie C2, the fourth tier of Italian football, and even stripped the club of its name, so that the new club was called Florentia Viola. All of the team’s players were allowed to leave on free transfers, including stars like Enrico Chiesa and Nuno Gomes, an option that most of them understandably took with only Angelo Di Livio, the tireless midfielder, staying loyal to the club in the lower leagues.

Fiorentina were effectively saved from extinction in 2002 by the Della Valle family, whose wealth comes from the shoe and leather industry, with Diego becoming owner and president and his brother Andrea handling the day-to-day running of the club. Having steadied the ship, the Della Valle brothers guided the new Fiorentina back to Serie A in just two years, albeit with a little good fortune.

The Viola won Serie C2 at their first attempt, securing promotion to Serie C1, but were immediately handed a place in Serie B for “sporting merits”, following that division’s expansion from 20 to 24 teams. This has never really been fully explained, but it is true that Fiorentina have spent almost their entire history in the top tier, twice winning the scudetto (1955/56 and 1968/69) and the Coppa Italia on six occasions. That year, the Della Valles further enamoured themselves to the fans when they bought back the right to use the club’s traditional name and shirt colours for €2.5 million.

"Prandelli - see you in the national team"

Remarkably, the team gained promotion the very next season, though they had to do it the hard way, winning a play-off 2-1 against Perugia after finishing sixth in Serie B. So, now they were back where they belonged – and this time they were debt-free. Having consolidated their position among Italy’s leading clubs, they made two important signings off the pitch in the summer of 2005, recruiting Cesare Prandelli as coach and Pantaleo Corvino as sporting director.

The team flourished with powerful centre-forward Luca Toni scoring a remarkable 31 goals in 34 appearances to help take them to an unexpected fourth place, which was enough to qualify them for the Champions League. Except it wasn’t, as Fiorentina were subsequently implicated in the Calciopoli scandal of 2006, after police uncovered a series of telephone interceptions that showed a number of major teams (also including Juventus, Milan, Lazio and Reggina) attempting to rig results by selecting referees that would be favourable to them.

Fiorentina were initially relegated to Serie B (here we go again) with a 12 point deduction, but on appeal were reinstated to Serie A with a 19 point deduction, which was finally lowered to a 15 point penalty. Even so, it looked for all the world as if Fiorentina would struggle to avoid relegation the following season, but, as always, the Viola proved to be unpredictable and surged to sixth place, thus qualifying for the UEFA Cup.

There then followed a purple patch (if you’ll excuse the pun) in Fiorentina’s fable, as they reached the semi-finals of the UEFA Cup, before being unluckily eliminated by Rangers on penalties, and then qualified for the Champions League after many years absence by finishing fourth in 2007/08, a feat they repeated the following season.

"Melo - strengthens the midfield and balance sheet"

The foray into the 2008/09 Champions League was unspectacular, as they finished third in the group stage, but the following season’s campaign really caught the fans’ imagination, as they finished top of a strong group, memorably defeating Liverpool home and away, before crashing out to eventual finalists Bayern Munich on away goals – one of which was palpably offside.

Since then, the spirits have been dampened somewhat, as the strong management structure has suffered a few blows. First, Andrea Della Valle decided to stand down from his role as president in October 2009, as he began to come under fire for his stewardship, partly for failing to reinvest the money received from the sales of Felipe Melo to Juventus and Giampaolo Pazzini to Sampdoria.

Although he reiterated his love for the club and indeed remains the majority shareholder, in an open letter to fans he lamented that the “climate” in Florence had changed dramatically since the takeover in 2002, citing a lack of faith in the family’s “project”, though this was also a reference to the perceived lukewarm support of the local council for a new stadium.

Although the team did well in Europe, the 2009/10 season finished on a low note for Fiorentina, as they only came 11th in the league, thus failing to qualify for Europe for the first time in four seasons. The pain was exacerbated when Prandelli left to coach the national team, leaving only Corvino from the managerial triumvirate that had been so successful.

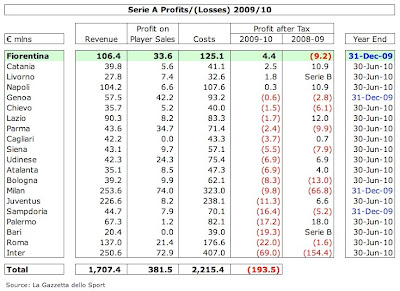

That said, they have been doing well off the pitch, so much so that last season they made more money than any other club in Serie A, though a couple of points need to be emphasised before people get too excited. First, the profit after tax was still fairly low at just €4.4 million; second, only four teams actually recorded a profit, the others being Catania €2.5 million, Livorno €1.8 million and Napoli €0.3 million, while the other 16 clubs all made losses.

The reality is that Italian football continues to be in a financial mess with clubs living well above their means, as they have been hit by falling crowds, accusations of corruption and occasional violence and racism, so being the most profitable club in Serie A is only really equivalent to being the tallest man in Lilliput. Despite the ever increasing revenue, largely driven by television money, which for the first time last season surpassed €1.7 billion, the combined losses of the 20 teams in Serie A amounted to €193.5 million and would have been even higher without the hefty €381.5 million profits on player sales, including the exceptional transfers of Ibrahimovic and Kaka to Spain.

Although it is true that Serie A losses have improved since the peak deficit of €536 million in 2002/03, last year’s figures are still nothing to write home about. In fact, the average loss over the last three seasons is almost exactly €200 million, which is nowhere near sustainable, especially in the era of UEFA Financial Fair Play. Reform is urgently needed, particularly in relation to the stadia, if Italian football is not to lose further ground financially against the other leading European leagues, though the return to collective selling of TV rights from this season is a step in the right direction.

Nevertheless, Fiorentina clearly deserve some praise for their efforts, especially as much of the improvement in their financial circumstances can be attributed to success on the pitch. In fact, Fiorentina’s revenue of €106.4 million is now the fifth highest in Italy, though it’s a fair way behind the traditional big four clubs.

The northern giants all generate more than twice as much revenue, mainly due to their very high individual television deals, though commercial income also plays a part, with Milan leading the way with €253.6 million, followed by their local rivals Inter €250.6 million and Juventus €226.6 million. On the other hand, Fiorentina’s revenue is in turn more than twice as much as competitors like Sampdoria, Udinese and Parma.

This has left Fiorentina just outside the top 20 of the Deloitte Money League, which ranks clubs in order of revenue, so they now sit happily in 21st position, a rise of five places over the previous season, ahead of clubs like Borussia Dortmund, Bordeaux, Sevilla, Valencia and Benfica. This is pretty good by most standards, but the league table also reveals the significant monetary advantage enjoyed by the leading teams with Real Madrid and Barcelona earning four times more income than a club like Fiorentina. To place the Viola’s recent achievements into context, when they narrowly lost to Bayern Munich in the Champions League last season, they were facing a team whose annual budget is three times as high.

Those of you that are particularly eagle-eyed will have noticed that the revenue figures used in the Deloitte Money League are lower than those used in the analysis reported by La Gazzetta. The reason for this discrepancy is that Italian accounts report gross revenue, while Deloitte only show the net income. In order to be consistent with other countries, I have adopted the Deloitte approach in my analysis, so have excluded the following: (a) gate receipts given to visiting clubs €1.7 million; (b) TV income given to visiting clubs €7.0 million. Subtracting this €8.7 million from the €106.4 million reported in Italy gives the €97.7 million in my analysis.

Hang on a minute – isn’t the figure that Deloitte uses for their report also €106 million? Well, yes, but this is simply a coincidence, as this is due to yet another complication, namely that Fiorentina’s accounts are based on a calendar year, unlike the vast majority of Italian clubs that close their books on 30 June to be in line with the football season. The adjustments made by Deloitte for this timing anomaly are enough to bring the revenue back up to €106 million. In any case, the themes and issues are very much the same, whichever revenue figure you take.

Last year’s profit was the first in the Della Valle era. Since they took over in 2002, the club’s accumulated losses had amounted to €62 million with the auditors noting that the deficit had to be covered each year by the owners. Still, any profit made by a football club is not to be sniffed at, so Fiorentina’s performance is not too shabby: €10.1 million profit before tax, falling to a net €4.4 million after tax.

However, this was a year when everything went well for Fiorentina from a financial perspective, so these results could be considered a best case scenario, as they benefited from two factors which are unlikely to repeat every year, namely Champions League revenue (€27 million) and very high profits from selling players (€28 million). Without these exceptional items, there is a €50 million hole in the accounts that needs to be covered by other means.

"Adrian Mutu - never a dull moment"

In other respects, last season’s profit and loss account is broadly similar to the previous year with revenue rising by €1 million, wages by €2 million, amortisation by €2 million and other expenses by €3 million. Indeed, if profit on player sales had been at the same level, the loss would actually have increased from €9 million to €14 million.

The largest loss in recent years of €19.5 million came in 2006, due to the special circumstances around Calciopoli, as bonuses agreed for reaching the Champions League still had to be paid, even though the football authorities rescinded the qualification. However, that was also a year when the club made a small loss from player transfers, which is a recurring theme for Fiorentina. In other words, when the club makes good money from selling players, this results in a profit (2009), if also accompanied by Champions League qualification, or a small loss (2007). In other years, when the books are not balanced by selling the family silver, the losses are larger.

In 2009, the net profit on sale was €27.6 million, which was made up of profitable sales (plusvalenze) of €33.6 million less loss-making sales (minusvalenze) of €6.1 million. On the plus side, there were three major sales: Melo to Juventus for €25 million (profit €17.7 million after deducting the net book value), Pazzini to Sampdoria for €9 million (profit 7.1 million) and Kuzmanovic to Stuttgart for €7.5 million (profit €5.7 million).

"Adem Ljajic - every man to his post"

Against that, the club made a loss of €3.3 million when they sold Manuel Da Costa to West Ham. The last big loss that Fiorentina made on layer trading was when they cancelled Japanese international Hidetoshi Nakata’s contract in 2006, which cost them €1.4 million. More happily, the club made good money the following year when they sold Toni to Bayern Munich €6.3 million, Reginaldo to Parma €3.8 million and Bojinov to Manchester City €2.1 million.

Clearly, Fiorentina are not the only club whose financial performance is heavily dependent on the vagaries of the transfer market, e.g. Palermo went from an €18 million profit in 2008/09 to a €17 million loss in 2009/10, almost entirely due to the profit on player sales falling from €50 million to just €1 million.

The other point worth noting, especially to those fans who are eager to see their club spend the money received from selling players, is that clubs rarely receive all of the cash upfront, especially in Italy where stage payments are the norm. For example, the €25 million fee for Melo was scheduled to be paid in three equal tranches of €8.5 million in 2009/10, 2010/11 and 2011/12.

In terms of their recurring business model, Fiorentina are much the same as other Italian clubs, earning the lion’s share (around two thirds) of their revenue from broadcasting with only 13% coming from gate receipts. In fact, due to their relatively low commercial income of around €20 million compared to the leading Italian clubs (Milan €63 million, Juventus €56 million, Inter €48 million and Roma €38 million), the reliance on TV money is even more pronounced.

Indeed, the Deloitte report lists Fiorentina as being the 13th highest club in Europe in terms of TV revenue with €69.7 million, which may surprise a few people, though this does include €22.4 million of money from UEFA’s Champions League distribution. Their domestic deal has quadrupled in value in the last five years from the €12 million in 2004 (in Serie B) to the €45 million earned last season. That’s impressive, but it’s still a long way short of the €90-100 million deals negotiated by Juventus, Inter and Milan.

That level of inequality makes it very difficult for other clubs to mount a realistic title challenge, which explains why Diego Da Valle was at the forefront of the campaign to change the system of clubs negotiating deals on an individual basis. He brought together a group of similarly unhappy club presidents, warning, “If Juve, Milan and Inter want to make a farce of Serie A, we can also play that game. We can send out boys' teams. We can make a nonsense of Italian football.”

That has helped bring about the replacement of this structure by a return to a centralised collective deal from the start of the current season. The total money guaranteed by exclusive media rights partner Infront Sports will be approximately 20% higher than before at over €1 billion a year, but it is still unclear what the impact will be on individual clubs’ revenue.

There is a complicated distribution formula, which will still favour the bigger clubs, though there is likely to be a reduction at the top end. Under the new regulations, 40% will be divided equally among the 20 Serie A clubs; 30% is based on number of fans (25%) and the population of the club’s city (5%); and 30% is based on past results (5% last season, 15% last 5 years, 10% from 1946 to the sixth season before last).

Fiorentina themselves have stated that there is “uncertainty” over how much they will receive, noting that this has caused them “considerable difficulty” in preparing their business plan, as there could be an “enormous impact” on their accounts. They are at pains to pointing out that they are one of the teams with the highest viewing figures on Sky, only behind the two Milan teams, the two Roman teams, Napoli and Juventus.

As we mentioned earlier, Champions League revenue has been vital to the club’s revenue growth, which can be very clearly seen in the above graph. Last year, this amounted to 28% of the club’s total revenue, largely due to the TV money €22 million, but also included gate receipts €3 million and sponsorship premiums €2 million. As the club’s own accounts say, participation in the Champions League is “important economically”. You can say that again. Next year’s turnover will be badly hurt by the absence from Europe’s premier competition, as almost all the money earned for the 2009/10 campaign has been booked in the 2009 accounts (including an estimate of the TV market pool).

It’s also worth noting that while the Europa League would help bridge the gap, it is nowhere near as lucrative as the Champions League. As an example, last season’s three Italian representatives (Roma, Lazio and Genoa) only earned around €2 million apiece compared to the average €29 million for the four teams in the Champions (Inter, Milan, Juventus and Fiorentina).

Like all Italian clubs, Fiorentina have struggled to grow match day revenue, which stands at only €12.8 million (net of €1.7 million given to away teams). In fact, the gross revenue actually dropped €2.3 million in 2009 from €16.8 million to €14.5 million, though there were valid reasons for the decrease: (a) the number of European home matches fell from 8 to 5; (b) more games against the top teams were played in the second half of the 2009/10 season; (c) more stringent restrictions to stadium access.

The average attendance fell from 31,509 to 27,248, though this is still the sixth highest crowd in Italy, behind Inter, Milan, Roma, Napoli and Lazio. Given the size of Florence compared to the metropolitan centres, this is really not too bad. In fact, Fiorentina’s gate receipts are not too far behind Juventus €17 million and Roma €19 million, though Inter and Milan are much higher with €39 million and €31 million respectively.

However, there is no doubt that Italian clubs need to find a way to improve their match day revenue, reducing their reliance on TV income, if they want to keep pace with their European peers. As an example, Real Madrid’s annual match day income of €129 million is almost exactly ten times as much as Fiorentina, while English clubs also earn considerably more, e.g. Manchester United €122 million and Arsenal €115 million.

Fiorentina have adopted a couple of new initiatives like building more “sky boxes”, launching family promotions and implementing a new ticketing system in partnership with TicketOne, but they really need a new stadium to make a step change to their revenue (and indeed their whole business model).

"Stadio Artemio Franchi with its tower of power"

The club has been playing at the Stadio Artemio Franchi since 1931, so there is a lot of history associated with the current stadium, which has a capacity of 47,282. However, built entirely from reinforced concrete, it is now outdated for modern football, even though it has been renovated on a number of occasions, including the 1990 World Cup when the running track was removed.

The need for a more “productive” stadium is why the owners launched the “Cittadella Viola” project in the Castello neighbourhood of Florence, including a new stadium, training centre, offices and retail outlets. Fiorentina described this as “a strategic priority and indispensable for the club’s development.” However, an announcement by Andrea Della Valle last October seemed to mark the end of the dream, due to lack of progress with the local authorities, “We’ve been fighting for the Cittadella since we first arrived, and we can’t anymore. My brother and I are tired and the city and the region just won’t accept our demands.” Never say never, but the club may have to look for alternative methods of increasing their revenue.

There is certainly scope for increasing the club’s commercial revenue, which actually slightly decreased in 2009 to €17.7 million. A new shirt sponsorship deal was signed with Mazda in January for almost €4 million a season, running for two and a half years until the end of season 2012/13. This effectively replaced the last paying sponsorship from another Japanese car manufacturer, Toyota, though in between Fiorentina had arranged a deal with the Save The Children charity along the same lines as Barcelona’s relationship with Unicef.

Despite the increase in revenue, other leading Italian clubs earn a fair bit more from shirt sponsorship: Milan – Emirates €12 million, Inter – Pirelli €9 million, Juventus – Betclic €8 million and Roma – Wind €7 million. They also receive higher sums from their kit suppliers than Fiorentina’s undisclosed agreement with Lotto Sports (Inter – Nike €18 million, Milan – Adidas €13 million, Juventus – Nike €12 million and Roma – Kappa €5 million). Although Fiorentina’s commercial revenue has been boosted in the last three years by premiums from their sponsors for qualifying for Europe (averaging €1.7 million), this is still a drop in the ocean.

As with every single football club, Fiorentina’s highest cost is the wage bill, which stands at €65.5 million. This has doubled since the return to Serie A (€32.4 million in 2005), though only increased by 3% last year. In fact, the important wages to turnover ratio is not too bad at 67% and has been maintained at this level for the last three years. According to La Gazzetta, many other clubs have much higher (worse) wages to turnover ratios, e.g. Bologna 94%, Inter 93%, Bari 88%, Sampdoria 85%.

This is evidence of tight management control and Andrea Della Valle has spoken in the past of an unofficial salary cap. Although he has said that this could be broken for a “special” player, rumour has it that this prevented the club from signing Alberto Aquilani from Liverpool last summer. Furthermore, Della Valle might even be looking to further cut the wage bill, as he warned that “the strategy of increasing costs to maintain a large squad to cope with participating in three competitions would not be repeated in future seasons.”

That said, Fiorentina’s wage budget of €65 million is the fifth highest in Italy, though none of its players are enormously paid (by today’s standards) with the highest earners being Frey, Mutu and Gilardino who are apparently all on around €2 million a year. However, this is still absolutely miles behind the “big boys”: Inter €234 million, Milan €172 million, Juventus €138 million and Roma €101 million.

Of course, a club’s total wage bill does not just comprise players’ salaries, though this was the largest element of Fiorentina’s 2009 costs at €40 million. In addition, there were €7 million for salaries of technical staff and €12 million bonuses, which were unusually high, due to the Viola’s European success. Interestingly, the accounts specifically note that part of the transfer funds received was allocated to cover higher salaries.

The other major player cost, namely amortisation, is again indicative of firm cost control. After a large jump in the first two years back in the top tier from €10 million to €24 million, it has risen very little in the last four years and now stands at €29 million in 2009. Again, this is on the low side compared to the Milan giants (Inter €65 million, Milan €41 million), but is around the same level as the other leading clubs (Juventus €34 million, Roma €24 million).

For the uninitiated, I should explain that amortisation is the annual cost of writing-down a player’s purchase price. For example, Alberto Gilardino was signed for €15.75 million on a five-year contract, but his transfer is only reflected in the profit and loss account via amortisation, which is booked evenly over the life of his contract, i.e. €3.15 million a year (€15.75 million divided by five years). Thus, the total cost of player purchases is not immediately reflected in the expenses, but increased transfer spend will ultimately result in higher amortisation.

Therefore, the fact that amortisation has not increased by much would imply that Fiorentina have not spent big in the transfer market and that is indeed the case, at least until recently, when there have been a few signs of higher expenditure, such as the relatively large money laid out on young forwards Adem Ljajic (€5.5 million) and Haris Seferovic (€2.1 million) . Following the club’s financial difficulties early in the millennium, Fiorentina were a selling club out of necssity, making good money on Rui Costa and Francesco Toldo, but splashed €93 million of cash in the three years after their promotion under the guidance of transfer guru Pantaleo Corvino. However, since then, the brakes have come on with net spend of only €34 million in the last four years.

This is one reason why the club’s debt position is so admirable. In fact, they have been debt-free for the last few years with net funds available rising from €5 million to €17 million last season. The Viola are much more stable financially than Milan or Inter, who have large bank debts of €164 million and €71 million respectively, which represents two thirds of the Serie A total of €352 million.

Of course, in Italy, you also have to look at the liabilities to other football clubs, as delayed payments on transfer fees are often used as a financing mechanism, but even here Fiorentina look pretty good. After many years of having net transfer fees payable (e.g. €26 million in 2008), they are now owed a net €2 million by other clubs.

As a matter of fact, Fiorentina have the strongest balance sheet in the whole of Serie A with net assets of €93 million, just ahead of Juventus, though it should be acknowledged that this is partly due to the owners’ support, as they have injected around €150 million of capital since the takeover in 2002, including €10 million in 2009 and €20 million in each of the previous two seasons.

Actually, most Italian clubs have made efforts to clean up their balance sheets with only four clubs (Milan, Bari, Roma and Inter) reporting net liabilities. Even though gross liabilities in Serie A amount to more than €2 billion, much of this is owed to others within the world of football through outstanding payments on transfer fees, while a lot is just incurred in the normal course of business, e.g. trade creditors, accruals, provisions, etc.

Fiorentina’s net assets would be even higher if a real value were to be applied to their players, who are shown at a net book value of €75 million in the accounts, but are worth considerably more on the transfer market – estimated at €181 million by Transfermarkt. Those players that have been developed by the club’s own academy actually have no value in the books, which is one reason why Fiorentina have devoted a fair amount of resource to improving their youth system. This is now beginning to pay dividends with the emergence of the likes of Michele Camporese and Federico Carraro, as shown by last week’s victory in the Primavera Coppa Italia, when they defeated Roma in the final.

Fiorentina are rightly proud of their financial results, which they say could lead to a genuinely self-sustaining club that is in line with the new UEFA Financial Fair Play rules, but the reality is that they still require the backing of their owners. A few years ago, Diego Della Valle explained this very simply, “We make money at Tod's (their business). In Fiorentina we lose money. It's our family's Sunday hobby.” In fact, his brother has said that the family would be willing to sell, if investors could be found that had Fiorentina’s best interests at heart and had the financial resources to take the club to the next level.

"Stevan Jovetic - the next big thing?"

So where does that leave us? At the minute, Fiorentina are indubitably the most profitable club in Serie A, but without the benefit of Champions League qualification and/or significant player sales, it is unlikely that they will retain this title for long. Although their fans will not want to hear it, that might mean selling one of the Viola’s prize assets like Jovetic, who was reportedly the subject of a €30 million bid last summer and interests the likes of the two Manchester clubs and Barcelona. Of course, that would almost certainly damage the club’s prospects of getting back into the Champions League, so it’s the usual dilemma: profits or performance?

That’s a difficult question to answer, as it’s almost impossible to have both, so maybe we should just congratulate Fiorentina on their successful rebirth, which somehow feels entirely appropriate for a team coming from a city famed for its Renaissance period.